April Barber was 15 years old and pregnant when she poured gasoline in the hallway of her grandparents’ Wilkes County home and flicked a lighter.

The ensuing fire claimed the lives of her grandparents, Lillie and Aaron Barber, the people who raised her.

April Barber and her then-boyfriend went to prison.

Their son, Colt, would grow up in Greensboro, raised by a family friend whom he calls mom.

More than 23 years later, April Barber wants a second chance.

Her attorney, Greensboro’s Don Vaughan, plans to ask Gov. Pat McCrory for clemency in her case, with the hope that he may commute one of her two life sentences and make her eligible for parole.

It will be a difficult case to make. McCrory gets 10 to 15 requests for clemency every day, and he has granted only three pardons since becoming governor in 2013.

People are also reading…

Barber will argue that she is a changed person. That she can lead a productive life outside prison.

"I have remorse every day for what I’ve done, for how everyone’s life has changed — mine, theirs and everyone else involved,"

“I have remorse every day for what I’ve done, for how everyone’s life has changed — mine, theirs and everyone else involved,” she said in a recent interview in the recreation room of the Southern Correctional Institution in Troy. “They were the two people that raised me. They were my parents, in essence. I made a stupid mistake.”

She will face skepticism.

“I’m sure there are those examples (of convicted people) who have come back and lead pretty full and useful lives,” said Dane Mastin, the former sheriff of Wilkes County. “But they all paid their obligations. She has not.”

• • •

April Barber was born in Wilkes County, the daughter of teenage parents who would be in and out of jail and prison her whole life.

Her mother, Sheila Barber, preferred partying to parenting, the way her daughter tells it. She served time for petty theft, drug charges and forging checks.

“Sheila was always in and out of my life,” April Barber said. “I was always her mother, and nobody was ever mine.”

Lillie and Aaron Barber were working-class people who adopted Sheila Barber when she was an infant. They were in their 60s when April Barber was born, but they adopted her, too.

“They took care of her better than I could,” said her father, Harvey Lee Moxley, who now lives in Winston-Salem. “Anything she wanted, they would get it for her.”

April Barber was a good student, and they hounded her about her education. Encouraged her to go to church, her father said.

• • •

April Barber met Clinton Johnson when she was about 14 years old and working in a summer job program for teens. He was just shy of 30.

Lillie and Aaron Barber were strict grandparents. So she and Johnson would sneak around. Sheila Barber helped, by signing her daughter out of junior high so she could hang out with Johnson.

“We’d take her where she wanted to go, give her a little money, and she kept her mouth shut,” April Barber wrote in a memoir about her mother.

Moxley didn’t like it, but there wasn’t anything he could do. He was in prison, serving time after being convicted for manslaughter and other charges.

April Barber was 15 when she got pregnant. She said her grandparents gave her two options: abort the child or they would turn Johnson in for statutory rape.

They were too old to take care of any more children. But April Barber did not want to give up her child.

“I always grew up feeling unwanted because I knew my mother had given me up for adoption. I didn’t want that for any child,” she said. “I just wanted to raise my child and be a normal family.”

She wanted her grandparents off her back.

She said Johnson bought the gasoline. She lit the fire.

• • •

It was a September evening in 1991. Lillie Barber, 77, was helping Aaron Barber, 83, take a bath when the fire broke out.

She escaped through a first-floor bedroom window, according to newspaper accounts of the court proceedings. She had burns on her arms, chest, neck and back.

“She was screaming that her baby was still in the house. She was talking about April. She wanted me to get April out. She didn’t know April had done it,” recalled Jack Shepherd, a neighbor who was the first person to arrive at the fire that night.

“I felt right then something was wrong. She could hear her grandmother crying and screaming in pain and hollering for her just as well as I could.”

April Barber said she tried to call the fire department, but the phone didn’t work.

“It was kind of one of those ‘what have I done?’ moments afterward,” Barber said. “At 15, it’s kind of a naive age. You have all the answers, and yet none at all.”

Shepherd and others tried to get into the house to save Aaron Barber, but the smoke was too thick. He died from smoke inhalation.

Lillie Barber went to the hospital, where she later succumbed to her injuries.

By morning, April Barber had confessed.

Mastin, the former county sheriff, said what she did was cold and calculating.

“It was thought out. It was planned, and there was no remorse behind it,” he said.

Johnson was convicted and given two life sentences plus 30 years for murder and arson charges. He died in prison.

Barber was tried as an adult, although she could have been tried as a juvenile. She pleaded guilty and received back-to-back life sentences. Because she was underage, she was not eligible for the death penalty.

“I realize two life sentences is very heavy for a 15-year-old, but she completely disregarded anybody’s life but her own,” Mastin said.

Shepherd, the neighbor, said he thinks the punishment should have been tougher.

“I think she should have paid ... with her life,” he said.

• • •

It’s hard to reconcile that April Barber with the one who now occupies a cell with two narrow windows in Southern, a women’s prison south of Greensboro.

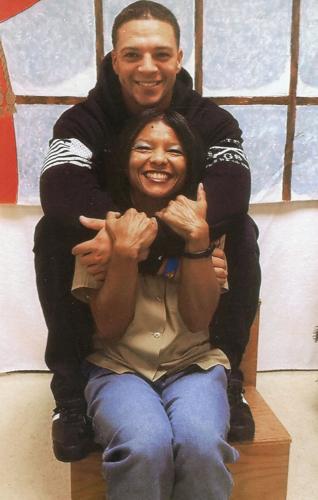

The petite 39-year-old is always after her husband, William Scales of Summerfield, 65, to eat right and get his exercise. They met while Scales was visiting his stepdaughter in prison.

“He wants to see me thrive. He wants me to have a life and serve a purpose,” she said.

She keeps up with her son, Colt Johnson, now a 23-year-old Marine who will go to Appalachian State University in the fall.

She has a four-page list of classes she has taken while serving her prison sentence — including getting her GED diploma, taking vocational courses and studying entrepreneur training. She dreams about opening her own combination gym-and-hair salon. Maybe in Greensboro, where she would like to move to if she gets out of prison. She is working on the business plan now.

She has written memoirs about her son and her fraught relationship with her mother, who died in 2003.

She runs and meditates and does yoga to keep her multiple sclerosis at bay.

“She served her time,” her son Colt said. “It’s time for her to move on with her life.”

Her father said she can prove to the world she is not the same girl that left Wilkes County in 1991.

“She’s not a kid now. She is grown and she done deserve a chance to prove to this world that she has changed,” Moxley said. “She’s gonna make something out of her life.”

• • •

When April Barber was sentenced in 1992, a “life sentence” was about 20 years. She will be eligible for parole when she is 55.

But she is hoping it will be sooner.

Her attorney, Vaughan, will help her petition McCrory for clemency later this year.

Vaughan will note that she has taken advantage of opportunities to better herself while in prison, that she was young when the crime happened and that her co-conspirator was twice her age.

Her family thinks Clinton Johnson influenced her decisions.

But she does not.

“I was old enough to make my own choices. I was old enough to know right from wrong,” she said. “I should have perhaps had a different influence, a better influence. But I am not going to blame anyone at this point. I take full responsibility for my actions.”

It will be useful for Barber to show she is remorseful and taking personal responsibility, said Mike Rich, an associate professor at Elon Law School.

But whether or not that will help her case with McCrory is uncertain.

Clemency “is one of those powers that is not frequently used,” Rich said. “In some ways that makes sense. It is a politically risky thing to do”

Barber said she can be a productive person outside of prison. She just wants that chance.

“I hope people see me for the person I am today and not who I was 20 years ago.”