by Ronald Clark, Jr. | Feb 19, 2020 | Inmate Contributors

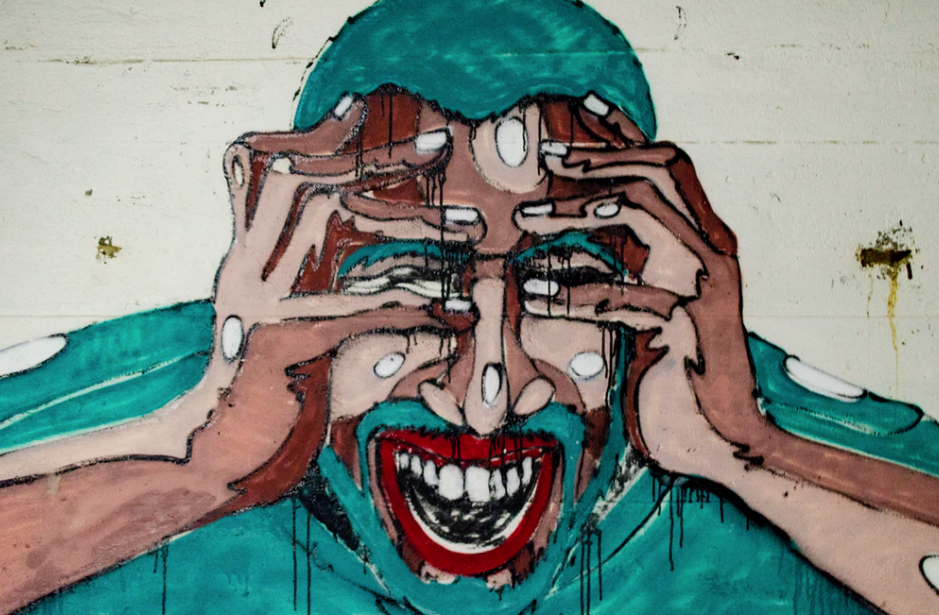

Physical mental and emotional torture. That’s what solitary confinement amounts to. Is this just my opinion from my own personal experience? No – this is scientifically proven. What I’m about to share is scientific testimony out of case law, which you can find on any legal website, under WILLIAMS VS. SECRETARY PENNSYLVANIA DEPT OF CORRECTIONS 848 F.3d 549 2017 U.S. App.LEXIS 2327.

“The Scientific Consensus”

The robust body of scientific research on the effects of solitary confinement, combined with the Supreme Court’s analysis in Wilkinson and ours in Shoats, further informs our inquiry into Plaintiffs’ claim that they had a liberty interest in avoiding the extreme conditions of solitary confinement on death row. This research contextualizes and confirms the holdings in Wilkinson and Shoats: It is now clear that the deprivations of protracted solitary confinement so exceeds the typical deprivations of imprisonment as to be the kind of”atypical, significant deprivation . . . which [can] create a liberty interest.

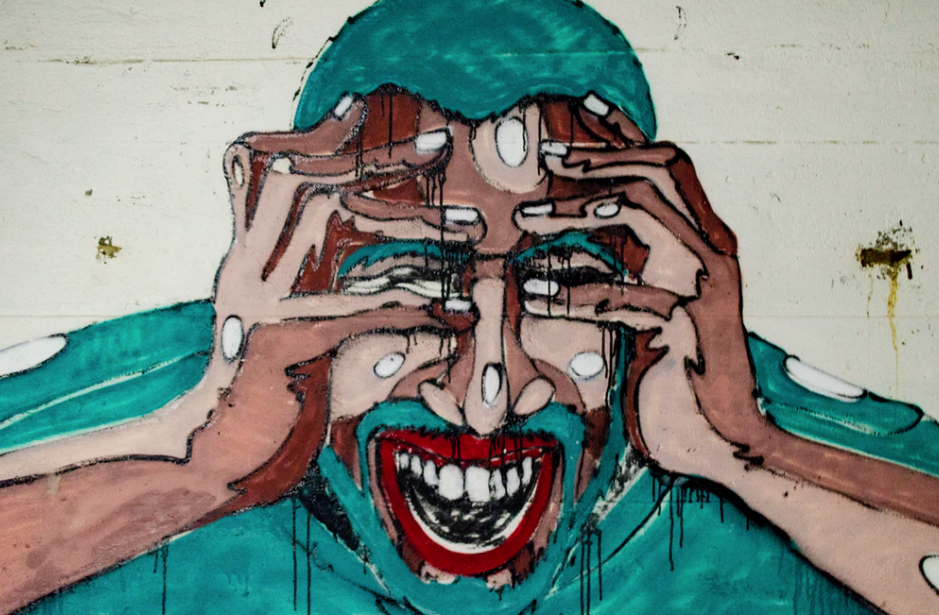

A comprehensive meta-analysis of the existing literature on solitary confinement within and beyond the criminal justice setting found that the empirical record compels an unmistakable conclusion: This experience is psychologically painful, can be traumatic and harmful, and puts many of those who have been subject to it at great risk of long term damage. Specifically, based on an examination of a representative sample of sensory deprivation studies, the researchers found that virtually everyone exposed to such conditions is affected in some way. They further explained that there is not a single study of solitary confinement wherein non-voluntary confinement that lasted for longer than 10 days failed to result in negative psychological effects. And as another researcher elaborated, All [individuals subjected to solitary confinement] will [. . .] experience a degree of stupor, difficulties with thinking and concentration, obsessional thinking, agitation, irritability and difficulty tolerating external stimuli. Anxiety and panic are common side effects. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis, hallucinations, paranoia, claustrophobia, and suicidal ideations are also frequent results. Additional studies include in the aforementioned meta-analysis further “underscored the importance of social contact for the creation and maintenance of self.” In other words, in absence of interaction with others, an individual’s very identity is at risk of disintegration.

Yes, the studies and case law speak volumes about the psychological torture that we are undergoing. I suffer with all of those symptoms. And I’ve often wondered why, not realizing it’s this cage that is causing them. Where is the evolving standard of decency that this country continues to speak about in the Courts, Congress, and Senate? You’re driving men insane! And then murdering them under this false concept of ‘equal justice.’ When everyone knows that a rich man will never enter one of America’s death chambers. Equality is a pipedream, a facade that America puts on for the world. We’ve seen it far too many times, innocent men and women have slipped through the cracks of America’s judicial system, and suffered irreversible harm, in these cages of doom. That’s all this is, a cage of doom! Warehoused for death. There’s no sugarcoating this hellish experience!

So when you wonder why I’m anxious, agitated, compulsive, depressed etc., etc. Well read the report again and again. And then imagine what I go through every single day. For not only do I struggle with this cage, but the fact that my co-defendant/childhood friend the triggerman, is on the street returned to his life, as I sit here, now second guessing myself on not accepting the plea bargain that was offered to me, which would have set me free in 2015. Yes .. should have, would have, could have! The fact still remains, that this cage, this treatment is inhumane and unbecoming of THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA! For this inhumane treatment is perpetrated in the name of God, justice, and the American way.

Just wanted to share and give you some insight into an experience that I pray you will never experience. God bless.

In peace and love, Ronnie

Ronald W. Clark Jr #812974

U.C.I. P-Dorm

PO Box 1000

Raiford, Florida 32083

by Eric Burnham | Feb 4, 2020 | Inmate Contributors

A legend lives no more. Tragically, Kobe Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, and 7 other souls lost their lives in a horrific helicopter accident. The Mamba is gone! I’m not an L.A. Lakers fan, but there are no word to express how I feel about the passing of Kobe, how his family and friends must feel. I grew up watching Kobe Bryant the basketball player, but after he retired from the NBA in 2016 — with a 60-point, drop-the-mic performance, I have learned so much more about the man, the husband, and the father through documentaries, interviews, articles, and talk show appearances.

This man had depth, to a degree that most people simply do not. While nobody is perfect, Kobe gave everything he was to everything he did. The intensity of his personality was often misunderstood, but everyday he tried to come as close as possible to perfection. The philosopher, Aristotle, once wrote “Excellence is not a singular act, but a habit” (fourth century B.C.). Excellence requires consistency. It demands effort and sacrifice. The pursuit of excellence will cost blood, sweat, and tears, and regardless of the arena, excellence separates the weak from the strong. The fruits of excellence will, quite automatically, transcend the arena in which they were produced, cutting across the boundaries of race, gender, education, or socioeconomic background. Excellence becomes a way of life, and nobody can honestly say that Kobe Bryant did not live an excellent life.

As an elite NBA superstar, one of the best to ever play, if not THE best, a champion, an all-star, and a technician, he awed millions around the world. He displayed not only an uncommon work ethic, but also unmatched skill that grew more lethal every season for 20 years. As a man, he certainly made some mistakes, but he overcame adversity and came back stronger. He gave his time and presence to all. As a husband, he remained committed, working through the tough times and shining through the good ones. For two decades he built a home with his wife Vanessa, and they had 4 daughters, one of whom, Gianna, was with Kobe in that helicopter. She was destined to be a basketball star herself — her father, the Mamba himself, gave his time and skill to nurture her love for the game. Indeed, it was as a father that Kobe perhaps did his best work.

People keep asking me why the death of this man I did not know has affected me so much. I cannot say, except that, in a world where almost everyone seems to be so stunningly self-absorbed, Kobe was not, and I admire that. I hear some guys around me talk about his mistakes, and it makes me sick to my stomach. They are doing to this legend the very thing they do not want done to them — defining him by the worst thing he has ever been involved with. We are all more than the sum of our successes or failures. Why can’t they see? I guess it is true: hurt people hurt people, but I wish they’d leave Kobe out of their psychosis. In the end, like Kobe Bryant, we will all be judged by how we responded to both our greatest successes and our biggest failures.

Again, I did not know this man, but he touched my life. I recently learned that, on the Sunday morning of his death, he attended morning Mass, flying in early to take communion. That warms my heart a little. Although no one can presume to know the heart of another person before God, it is good to know that Kobe and his daughter knew God in their own way. Perhaps God was simply ready to bring them home. Either way, Kobe displayed the heart of a warrior, and for a brief period of time, we were all able to see what that looks like.

Kobe Bryant taught me that if I want to impact others positively, I must care about them even more than I care about myself. Not in the traditional I-gotta-get-mine-let-me-help-you-get-yours type of narcissism so pervasive in contemporary culture, but in ways that develop my own natural talents and gifts, allowing me to become the man I was designed to be. That is the essence of discovering purpose. I always say, “If you wanna shine when everybody is looking, you gotta polish when nobody is looking.” Kobe exemplified that. Thank you, Kobe Bryant, for all you were. The world is a little better for having witnessed your life, and a little darker without you. Good night, Mamba. We will all miss you. My prayers go out for your family and the families of all those who lost their lives in that helicopter. Indeed, there are… no words.

by Eric Burnham | Jan 16, 2020 | Inmate Contributors

The United States of America, land of the free and home of the brave, often feels more like the land of the isolated and home of the cowardly tweet. We are more divided than at any point in my lifetime. It seems to be more than a mere lack of unity as an expression of national boredom. No, society is increasingly fragmented in deeper, more complex ways than at any point since the Civil Rights Era. Social structures quake as spreading fissures splinter national identity along lines of race, gender, sexual orientation, political ideology, educational background, socioeconomic class, and even traditions. The resulting fiefdoms are profoundly fragile as individual identities overlap, causing tension within.

Sure, these have always been sticking points of disharmony to varying degrees. In fact, one could convincingly argue the stress created by pluralistic differences has been the thread used to stitch together the very fabric of social progress in the United States since the beginning. Conflicts emerged in opposition to oppression, racism, sexism, worker’s rights, and competition for limited resources. And we are — or should be — proud of those conflicts, for they symbolize hard-won victories of the human spirit and goodness, and, yes, social justice. However, it has been quite some time since we have witnessed the level of vitriolic rhetoric, hatred, and vengeance seen so regularly today. It has also been quite some time since we celebrated together how far we have come in under 250 years. And as a consequence, Americans are retreating into their own private worlds, increasingly detached from those who are unlike themselves.

Individualism and the subsequent stratification of society has always shaped Western culture, and contemporary times are no different. But in years past, the concept of life in a bubble was reserved for the elites. In that regard, times have indeed changed. To be sure, in many ways the post-modern aristocracy is much like its pre-Enlightenment cousin. The nobility, although a mostly elected ruling class today, operates within the power structures of a bloated government while continuing to take orders from the clergy. Only today’s bishops serve the Church of Money and Fame, for who could argue that the deification of the dollar has not shaped current social and political realities? Yet, the peasantry, the rest of us who do the majority of the working and buying and living and dying in this country, have only recently gained access to life in the bubble. We used to be excluded from that paradise.

Everyday Americans are now born in a bubble structured by the ubiquity of technology. Many do not know anything else. All their needs are met within. They need not communicate with outsiders — news, education, and even general services are all consumed from preferred outlets that reinforce distinctions of worldview. The very dissemination of information, bought and sold to be sure, is a process of encoding ideas into the differential vernaculars within the different types of social bubbles. Ideas like privilege, racism, diversity, nationalism, and history, along with many others, mean one thing in one bubble and something completely different in another, galvanizing disconnections.

A tornado of money and technology has left in its wake a barren environment in which people with fascinating and profound differences surround each other, yet the politics of identity keep them from being able to acknowledge any level of similarity or sameness of experience. And the commodification of victimhood has made enemies of good people by normalizing a race to the top of Mt. Marginalization in an effort to secure the most cultural capital, decreasing social stability in the process.

Anger and rage are the most popular currency, the only communication between bubbles. The objective is to deplatform, silence, and destroy the opposition. Purveyors of thoughts, words, or ideas that do not perfectly align with every intersection of perceived injury, oppression, or objectification are banished from their bubbles. No discussion takes place, no reciprocation within a marketplace of ideas. Dissension is received as a personal attack, violence against the sanctity of the bubble, and therefore, must be punished. Nothing is sacred. Even humor is constrained, forced to pay the toll of scrutiny to the self-appointed arbiters of bubble culture — they stand at the gate armed and ready to defend against nonconformity.

Our bubbles started out as safe spaces, the environments where we could decompress and allow the anxiety of living in this hateful world to settle. They have now become prisons, holding us hostage, insulating us from those competing ideas that would expose the flaws in our own. That safety has crippled us, stolen authentic emotional experience and replaced it with a kind of manufactured emotion that has systematically removed empathy, concern, and compassion for those unlike ourselves, those who reside in different bubbles. Legitimate attempts to understand, even to love and accept those who are different than us or to bear the weight of their struggles or even to allow them to understand us is far too risky. Real love is too messy, and the fear of rejection from our own kind too real, so we hide away from uncomfortable realities, too afraid to be vulnerable. After all, our own bubbles are strange enough. But doesn’t this bubble effect feel somehow wrong? It does to me.

by Martin Lockett | Jan 15, 2020 | Inmate Contributors

When I came to prison, it was commonplace for people to meet up at someone’s house for a get-together to watch the Super Bowl or simply hang out and converse. When it was someone’s birthday and they lived quite a distance away, it was standard practice to call and wish them a happy birthday. In fact, if you can imagine, people called their friends and family members on a regular basis to just catch up with one another, check on those they love and let them know they care. As time and technology would have it, this now appears to be an era of the past that may never be resurrected.

The advent of prominent social media outlets such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to name a few, have revolutionized the way our society communicates and interacts even with those who are closest to us. This is a foreign concept to someone like me who has been incarcerated for 16 years and found camera phones to be space age technology when I started my sentence. But this is the way of the world and it will inevitably become a normal part of my daily life when I’m released in 2021. But I say this with some reluctance as I can readily see the disadvantages that accompany this luxury.

It’s obviously a great thing to be able to connect with people you wouldn’t otherwise due to distance or inaccessibility attributed to busy schedules that include work, kids, and daily life affairs. Social media outlets allow grandparents to see pictures of their grandkids as they grow up, and friends to keep up with the lives of their friends and acquaintances from high school that they likely would not otherwise. The many advantages of social media are uncontestable, but at what cost? What do we give up by having these advantages at our fingertips?

It appears that so many in today’s society have become overly reliant on social media for their “social interaction,” and have given up on or severely limited connecting with people face to face. They find themselves so engrossed in their Facebook pages that it no longer matters to go to Grandma’s house with the kids and sit with her for a couple hours to catch up, let her see and hug her grandkids, and show her that she’s worth your time. We no longer feel the need to court those who capture our interests at the mall or grocery store because we know it’s much easier to join a dating site or meet someone on Facebook and cut to the chase, have our immediate interests met with very little effort, never mind taking the time to get to know someone for who they really are. We assume sending a text to say we’re thinking of someone near and dear to us adequately conveys that sentiment, but we lose the tone and sincerity that can only come by them hearing our voice. We forfeit the opportunity to look them in their eyes when talking to them, allowing them to reciprocate and connect with us on a personal level when we communicate through social media. We lose the intimacy and personability that can only be transmitted through old fashioned face to face (or at least voice to voice) contact.

For me personally, I will admit that for years I was not a fan of the prospect of using these sites when I got out – until about two months ago. Because I will immediately look to brand myself as a credible public speaker upon my release, I would be a foolish, arrogant caveman to go at it without utilizing these tools. However, a part of me still very much opposes the idea of relying on them for personal contact with those I consider loved ones because I don’t want to depend on them for that sacred connection. During all my years in prison, I have called them and had stimulating conversations, filling them in on the latest with me and finding out what’s been going on in their busy lives. We laugh, cry, and everything in between. Would we have gotten this through Facebook? Why give this up just because my circumstances will change? I can still preserve these special moments by operating the way I have for all these years when it comes to connecting with those closest to me and even with casual friends. Sure, some may think I’m weird when I call them just to chat, but that’s okay because something tells me when they hang up, they’ll appreciate that I did. Something about physical (visual or audible) human contact makes us feel good on a soulful level. This could never be replicated through a screen and keyboard.

This is not to disparage anyone who finds great social value in the various opportunities provided by social media outlets, but the dangers of isolating and disconnecting more and more from physical human contact cannot be overstated. Perhaps there are also many who have found a happy medium between both forms of interaction. I certainly hope to be counted among them.

by Eric Burnham | Jan 14, 2020 | Inmate Contributors

Being incarcerated for any length of time can be a brutal, psychologically taxing experience. As of this writing, I am 40-years-old, and I have been incarcerated for 19 years, roughly 48% of my life. And while that may be eye-popping, it is important to remember that I am not the victim here. I hurt others, and there is no getting around that truth. My own behavior, my selfishness, my violence put me in prison. I deserve to be in prison, but I don’t ever want to be a man who belongs here.

My self-centered behaviors, my “doing” flowed from my inward state of “being.” I was broken inside. Only bad people consistently harm others in physical, material, and emotional ways. I was a horrible person — no singular act of violence led to my incarceration; it was a self-centered lifestyle that allowed violence and criminal activity to be acceptable, made increasingly worse by my self-hatred, which I self-medicated with copious amounts of drugs and alcohol. I hated who I was, but I don’t hate who I am. I’m not the same person today.

During my journey, I have thought much about how a bad person can become a good person. Is it even possible? I think so. I believe people can change. I’m certainly not saying I have achieved such a monumental feat, but I have arrived at a few foundational conclusions about what having strength of character means, which is such an abstract and confusing concept that it can make my head swim. It is so difficult to define. It is also extremely difficult to find in prison.

Personally, I don’t want to hurt anyone ever again — that is a top priority in my life. And a long time ago I realized that accomplishing that involves not only putting off my old patterns of “doing,” but also putting on a new way of “being.” If I want to be a good man, then it is my responsibility to figure out what that means.

Although admittedly complex, I feel like the characteristics of a good man are fluid and flexible, while paradoxically remaining absolute and irreducible. Whether incarcerated or not, a good man exemplifies courage, honesty, responsibility, patience, tolerance, high standards, kindness, mercy, loyalty, integrity, authenticity, and honor. These are not specific acts of doing; they are traits that determine how a person will act and react. They involve being. And while this may seem an impressive list, they are merely words. What they actually mean is incredibly elusive and slippery. They may engender strong, positive feelings, but what do they look like in action? This has been a difficult question for me to consider.

For example, courage is often subjectively determined by one’s view of the situation. Yet at its core, courage is not paradigmatic; it is objectively defined, although its application or expression, perhaps, may be situational. Courage is a commitment to face a threat, rather than run from it. Yet, even threats are subjectively determined, right? I mean, I’m not really afraid to fight. Some guys are, but I am not. However, I am quite fearful of appearing weak to others. For some, a willingness to fight when afraid takes courage, but for me, a willingness to walk away takes much more courage.

Prison culture has warped values and twisted social norms. There are times when you must fight, but most often, you have a choice. Yet, to walk away often appears weak. To speak up against racism or to encourage others to find peaceful, non-violent solutions to interpersonal conflict can appear soft, a weakness to be exploited. Therein lies my dilemma — to be courageous, for me, runs against the values of my environment. Decorated U.S. Army General George S. Patton (WWII) has been credited with saying, “Courage is not the absence of fear but the mastery of it.”

Consequently, for me, physically fighting, using violence to appease my bruised ego, essentially failing to defend my values, is a cowardly act, a selfish act. Courage, then, involves the fortitude to keep from being shaped by prison culture while simultaneously being defined by it.

Honesty has similar elastic qualities. Honesty involves far more than simply telling the truth and not lying, right? I mean, we all know that annoying cat who constantly embellishes in order to impress others and garner affirmation, basically by force. But as a character trait, honesty requires acknowledging mistakes and taking responsibility for my actions, rather than relying on clever duplicities in an effort to avoid consequences. Honesty involves resisting the temptation to use deception as a tool in order to defraud others for personal profit. The fruit of honesty, over time, is being viewed as a trustworthy person.

In prison, I see incredible dishonesty all around me on a regular basis. Guys may be “honest” (so called) with their “homies,” but consistently dishonest with everyone outside of their immediate social circle, and even themselves, especially when caught doing something against the rules. In my opinion, honesty is not a situational ethic — it must be the standard. I don’t need to “rat” on anyone in order to be honest, but I do need to be real with myself and others about my own actions. If honesty is not the standard, I am ultimately incapable of having character free from deceit.

That leads seamlessly into the concept of responsibility. As a character trait, responsibility involves dependability, fortitude, determination, and acceptance of consequences. I would go so far as to say that responsibility is the hallmark of adulthood, the foundation of everything. A good man is responsible for not only himself, his words and actions, but also those in his care, his family, friends, and all those affected by his decisions, words and actions. A responsible man will, at times, be willing to sacrifice his own needs or desires in order to keep from negatively impacting others. He is also accountable to his own conscience and willing to answer for his behaviors, whether they are right or wrong. He readily acknowledges his mistakes and takes an active role in righting his wrongs.

I really feel like patience and tolerance go hand in hand — A man who aspires to be good will patiently seek to understand others before making judgments about people and situations. As a tutor in the Education Department, I battle my own impatience often when I teach a challenging student algebra, paragraph writing, or even the structure of the U.S. government. Most men in here are not as educated as I, and if I genuinely want to positively impact them, I must exercise tolerance. By patiently enduring their mistakes as they learn, helping them to be okay with the trial-and-error process of growing, I learn humility, and the ensuing tolerance transfers to my view of everyone who is different than I, regardless of age, race, ethnicity, or educational/socioeconomic backgrounds.

It is not easy to set aside my personal biases in order to positively impact others. It is volitional, a choice, and I think the ability to do so flows from having empathy toward them. Others may think, feel, and act differently than I; they may have different beliefs or arrive at different conclusions about faith, politics, or reality itself, and to be okay with that requires not only tolerance, but also the kind of patience that fosters personal growth, knowing these differences do not threaten my own uniqueness.

I think a good man must have high standards as well. He will not always live up to them, of course, but he will do his best to adhere to his ideals. Standards of behavior, speech, and work ethic flow from self-discipline and commitment to growth. It is not easy to be a man of high standards, but it is easy to tell those who have them from those who do not. For example, I have seen cats in here erect personal standards for the explicit purpose of being seen doing so, creating the structure of their mask. Yet, behind the meticulously designed facade, they feel entitled to exercise no true boundaries, no morals, ethics, or universal code of conduct whatsoever. They are sharks who feed on others. I believe a good man refuses to do that. The outcome of a man without standards is both predictable and inevitable.

In my opinion, mercy and kindness run together as well. You cannot have one without the other. Mercy can be defined as entering into the experience of another and by doing so, feel moved to help. Mercy is love in action. A merciful man is one who stoops to conquer not only himself, but also another’s pain and suffering if he can. In prison, this type of kindness is very difficult to witness because it doesn’t happen much — it is just too risky. Genuine kindness recognizes the need for simple things like generosity, a smile, or even holding back bitter words, but it also includes the far bigger idea of not being emotionally or physically dangerous to anyone, which, in prison, is viewed as weakness to be exploited. Therefore, one must know how to stand up to the dangerous while being kind to the harmless. Mercy, in prison, is taking the time to know the difference.

Ahh… loyalty — what an overused word. Almost everyone wants loyalty, but so few are willing to give it in return. I think a good man is willing to pay the price for remaining loyal to his loved ones as well as his own ideals. Loyalty involves allegiance, an allegiance of commitment and faithfulness. When the inevitable conflict arises between loyalty to loved ones and loyalty to personal values, I feel like a good man would have the backbone to challenge loved ones about dishonesty or immoral behavior while simultaneously supporting them, which can be arduous and painful. Ultimately, however, loyalty to loved ones means not doing things that harm them and making sure they are protected, as well as playing an active role in ensuring that loved ones feel the comfort of that loyalty. Loyalty leaves no doubt.

Integrity is yet another murky, often misunderstood attribute. Not only is it the quality of having strong moral convictions, but it involves the ability to put them all together into blended functional properties that can be consistently applied. I can believe that courage, honesty, kindness, and loyalty are valuable traits, even admirable ones, but without the capacity for practical application when tempted to do the opposite, they are merely good ideas. It has been said that integrity means doing the right thing even when nobody’s looking. The only way to do that is to know what the right thing to do is — and to make doing it habitual.

A good man, with unquestionable strength of character, is authentic. There is no circumventing this. He is not phony; indeed he cannot be. He is comfortable in his own skin. Above I mentioned the mask that some wear — being authentic means not wearing a mask. A mask hides the beauty of the soul. Authenticity allows the unique beauty of the soul to shine into the world.

The dictionary defines authenticity as denoting an emotionally appropriate, significant, purposive, and responsible mode of human life. I view it as harmony between my inner life and outer behaviors. It is congruency of face — an authentic man is the same regardless of those around him. In prison, I watch so many cats alter their beliefs and behaviors in order to conform to those around them. To me, that inconsistency of character displays not only profound insecurity, but a distinct lack of personal identity as well, leaving them conspicuously untrustworthy.

Perhaps the most difficult trait to define, and therefore to achieve, is honor. Again, the dictionary holds honor to mean adherence to what is right, a morally upright standard of conduct. However, the term dishonor does me no favors when it comes to understanding — it means to have lost all claim to the good opinion of one’s peers. Consequently, I’m left to infer honor is defined by adherence to a socially accepted set of values. Yet, what those standards are depends upon the moral attitude of the majority. Then context matters, and in prison an apparent binary social code exists. One code is honorable to wider society and dishonorable among those encapsulated by prison culture; the other is honorable within the prison environment but dishonorable to wider society. That is how it is usually framed, but I don’t think it has to be so.

This squeeze between cultures can be a tight spot, making the formation of good habits difficult. The overwhelming majority of guys in here will choose the immediate gratification of acceptance within their environment. Yet, I want to be honorable, a man who epitomizes all the traits of a good man I’ve listed here, so the choice is clear for me. It is simple, but it is not easy. I am far from perfect, but I know who I want to be. And I’m finding more and more that striving to be a good man, even in prison, can be done. It is even respected when done right, with pure motives.

All this seems so idealistic, so utopian, doesn’t it? However, this type of strength of character exists in the world. It is not a myth. The very fact that it seems to be is evidence of how elusive truth and goodness have become. Good men exhibit these traits everyday, albeit imperfectly, but to be imperfect while straining for excellence sort of captures the human condition, does it not? And those men who strive to live up to the ideals described here inevitably enjoy a deep sense of justice, purpose, and self-respect, which in turn, garners the respect of others. Imagine professional athletes: They never stop chasing perfection, never stop working to get better. Good men pursue truth, love, and hope with a contagious zeal that impacts everyone around them in unfathomable ways.

While not intended to be exhaustive, I hope this writing has conveyed effectively my thoughts about not only what it means to be a genuinely good man, but also how difficult it has been for me to understand just what that means. I know right from wrong, to be clear, but I’m talking about more than that. I’m talking about impact, transformation, and giving back. A man who only consumes and never gives back is most certainly a nickel out here looking for a dime. All the negative traits I observe in prison moves me to constant personal reflection in order to root out any of them I see in myself. After all, I am in prison, too, encapsulated by my environment just like everyone around me. I guess it’s true what they say: The same boiling water that hardens an egg softens a potato. It all depends on my response. And where I stand does not have to depend on where I sit.

by Rick Fisk | Jun 13, 2019 | Inmate Contributors

Texas prisons are not cool

‘Cause most of our feelings, they are dead and they are gone

We’re setting fire to our insides for fun

– Daughter – Youth

Texas prisons are not cool in the summertime. The first year I spent in a Texas prison was in 2015 and I began my stay in the late fall at the Holliday unit in Huntsville. In November that part of Texas is typically cold and rainy. It can warm up into the 80s on an occasional autumn day. By April, when it is still cool in the rest of the US, the daily temperature in Texas and the south can reach 90 degrees Fahrenheit. By June, its sweltering.

I remember back in 2011 when Austin suffered a record heat wave. The temperature met or exceeded 100 degrees for more than 100 consecutive days. I spent as much time indoors that year as I could. When I did go outdoors it was to quickly enter an automobile accessorized with cold A/C. That same year 10 Texas prisoners died from heat stroke.

In 2015 when the heat of Texas strove toward its August peak, I had no such luxury. I was stuck, along with the majority of Texas’ inmates, without air conditioning in the sweltering heat.

To mitigate heat, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice installs fans in dorms and common areas. An inmate living on a unit having individual cells or dorms with single bunk living areas can buy a fan from the commissary for $20.00. Indigents are right out of luck, though the Texas CURE has provided fans to prisoners for many years. On the Holliday unit, a transfer facility with common dorms, inmates weren’t allowed to purchase personal fans because there were not enough outlets to supply the required power.

The Holliday unit is one of many intake facilities in Texas. Similarly constructed units are Middleton, in Abilene, Garza East and Garza West, both in Beeville, and Gurney in Palestine. The state built these units as part of a rapid expansion of the Texas prison system during Ann Richards’ administration.

As the Texas Monthly wrote in 1996:

Exploiting the cloud cover of “urgency,” prisons were built poorly and at an exorbitant cost. Some 12,000 “emergency beds” were thrown together in 180 days at the height of the hysteria in late 1994. Those particular prison units have a life expectancy of about twenty years, as opposed to the fifty-to-seventy-year life expectancy of the standard TDCJ prison; they are nothing more than minimum-security warehouses, and yet they carry the price tag of maximum-security prisons. Construction of the $10.3 million Ama-rillo meat-packing plant was also deemed for some strange reason an “emergency” back in 1994, a decision that cost the taxpayers probably an extra $1 million even though the facility was built partly using free inmate labor and even though it still lacks essential (and expensive) items like grease traps and bar screens.

These intake facilities still exist, more even than I have listed here, some 10 years beyond the time that TDCJ officials scheduled them for replacement. The corruption in the system was so rampant that lobbyists at that time figured they had an unlimited supply of taxpayer money. They believed they’d easily be able to convince the legislature to provide funds for shiny new prisons. Since then, there’s been some backlash nationwide over mass incarceration that hasn’t quite reached Texas. The inmate population back in 1996 was 129,000. Today that number is 160,000.

TDCJ built the units with steel girders, siding and roofs rather than the traditional brick and mortar walls and asphalt roofing found in more permanent units. As a consequence, the temperature in the dorms can exceed as 130 degrees in the summer. It’s a bit like living in an outbuilding or an Easy Bake oven. I showered two or three times a day just to get my shorts and t-shirt wet. This had limited benefit due to the nature of Huntsville weather namely, the constant high humidity which thwarted the cooling effects of evaporation.

If I were younger it probably would have been less stressful. I survived obviously but many Texas inmates haven’t and the average age of prison inmates increases each year. I saw men processed at Holliday who were eighty and older. The geriatrics had a difficult time with the heat.

TDCJ has been running from the A/C issue for years and in 2018 lost a federal law suit filed by inmates on the Wallace Pack unit. In the suit, which cost them an estimated $7 million, administrators claimed that adding A/C to the unit would cost between $22 million and $120 million. These figures were apparently only for the benefit of the jury (who don’t appear to have been fooled). After losing the law suit, they’ve revised those numbers down to about $4 million per unit. They could almost complete the upgrade of two units for the amount they spent fighting the law suit. With a total operating budget of $3.3 billion, (pdf) they could, at $4 million a unit, add A/C for all 155 units and barely make a dent in the total budget. Texas prisons are not cool for inmates but pigs have it made.

One of the early efforts TDCJ made to reduce the heat stroke problem was to make an educational video about dehydration and heat stroke. I remember my annoyance as they rolled these videos out. As with everything in prison watching the dehydration/heat stroke video was mandatory. Just another 20 minutes out of my day but it was the principle. Did they need to show it every 90 days? The video taught us how to drink water, how to gauge the color of our own pee and to consider when it might be necessary to sit in a respite area. These respite areas were places on the unit where A/C was installed. The hallway near the warden’s office, the infirmary or the education building.

The guards who work at TDCJ did not seriously consider inmate’s request for respite. Because they have been conditioned to treat every inmate request as though it is a ploy to achieve an ultimate escape, they would initially push back on these requests. When the Pack unit lawsuit started winding its way toward trial, administrators fearing more lawsuits encouraged the officers to take heat-related requests seriously. This had limited success.

For instance, keeping the coolers supplied with ice and water added responsibility to already full plates. The staff might pay closer attention to the issue if units were at full capacity. But with some units staffed below 50%, keeping coolers full is a low priority. At one unit I was on, the staff rate was 46% of optimum and we’d spend hours without cold water. Officers did not supply inmates tasked with refilling the coolers with proper gloves and equipment that would prevent cross contamination. After I watched the coolers filled once or twice, I couldn’t drink the water from them except in extreme circumstances. AI has received feedback on the Texas heat from some of our inside voices and published it here.

It’s nearly summer. In Texas especially, the inmates will have a difficult time staying cool. This discomfort up to and including death, will be a risk all the way past August. And TDCJ is even now playing games over the issue of A/C. Please consider contacting the Texas CURE and helping an inmate get a fan. Better yet, adopt a Texas inmate, especially if you’re in Texas. Texas prisons are not cool but they do have A/C in the visitation areas.

by Rick Fisk | Jun 11, 2019 | Angel Voices

Mary Ann MgGivern writes in the National Catholic Reporter:

[…]I was on the elevator with one of the governor’s aides, who said, “Oh, yes, the governor is committed to addressing mandatory minimums.”

I said, “For violent crimes?”

He said, “Oh, not violent crimes, that’s another matter. That’s different. I don’t know that there’s any appetite for reducing sentencing for violent crimes.”

Let me tell you, dear reader, that Missouri sentences are longer than most and that reports like those detailed in the America article find long sentences make things worse, not better. They don’t rehabilitate or prepare the person for work and family reunification. They just punish and punish and punish. They cost the family and the local community and they are expensive for the state, too.

But what the young aide, new to the job as our governor is new to his job (our elected governor was forced to resign), doesn’t realize is that the mandatory minimums he wants to reduce or even eliminate are generally tied to violent crimes. That’s what triggers them. So, say some years ago you hijacked a car, got caught, went to prison for five years, and years later you were arrested on two counts of drug possession. That triggers the mandatory minimums. Even if the third crime is 15 years later, like one client of mine who had been off parole for years but stole a lawn mower to support his drug habit. He was sentenced to 17 years in prison for that theft.

Besides writing on prison issues Mary also writes to several prisoners. She’s an angel. We keep discovering them in our real and virtual travels.

by Martin Lockett | Jun 11, 2019 | Inmate Contributors

This past week came with one of the biggest shocks of my fifteen years of incarceration. My unit (‘incentive housing’ with extra privileges for those of us who have exhibited at least 18 months of clear conduct) was inspected by the administration. We had been duly warned not to have any extra clothing or bedding when they come lest we be removed to another unit immediately. Such a move would force us to give up all of our luxuries such as all-day phone access, microwaves, access to hot water to heat up canteen food items, soda vending machine, etc. I’ve completed all 15 of my years of incarceration without receiving a single write-up. In other words, I know how to follow the rules, so when they warned us, I was already in compliance.

They came last Thursday, as promised, and began tossing extra clothing from people’s cells. I knew all those in violation would be removed from the unit. I’m thinking, “Why would they still have extra clothing?! They knew they were coming!” Then they got to my cell and tossed out a sheet, “Oh no,” I thought. “They got my cellie’s extra sheet at the base of his bunk” (he’s on the bottom). At that point I was worried I would lose my cellie and be forced to play the “cellie lottery” where we have no idea who they’re going to put in our cells. After all the dust settled, they moved 40 guys that very night!

The next day we all knew it still wasn’t over because we’d heard they were coming to move 11-20 more! I thought this was strange because why would there be a question as to how many would be moving? If you’re in violation, you’re in violation.

I came back from work at 10:00 am and asked the officer to pop my door. He said, with a list in his hand, “Are you A or B bunk?” I started worrying about my cellie, but I answered, “I’m A bunk.” He delivered the devastating blow: “You’re moving!” Shocked, incredulous, and staggered, I responded, “What? How? I didn’t even do anything. They took nothing from me.” He gave the typical contrived response most do in that situation: “I’m just doing what I’m instructed per the captain. I need you to start packing.”

Deflated and dejected, I packed and headed to another unit for the first time in the five years I’ve been here. No one cared to hear my claim of being innocent of this infraction. The administration needed ‘examples’ to send their message that they would no longer tolerate rule breakers, so anyone would do. All attempts made by my now former cellie to set the record straight by taking ownership for the confiscated sheet were met with apathy. A meeting was held by the administration, and a 90-day ban for returning to the unit was implemented for all 56 of us who were banished – guilty or not.

Needless to say, it’s been a huge adjustment for me. Everything from when I can use the phone, get hot water to cook, to even when I can get a shower, has changed. Through this ordeal I have felt wronged, indignant, and helpless. But after the initial shock and adjustment took hold, my true character, mettle, and resiliency kicked in.

In considering what has happened to me and putting it into its proper perspective, I accept it as something I have no control over. In doing that, I choose to not allow it to consume my thoughts or drain my energy. Instead, I consider it an opportunity to test my ability to adapt to and handle unexpected adversity well and appropriately. How often do we blow up, make rash decisions, and create mountains out of mole hills when sudden hardships afflict us? Then we reflect on it later and inevitably regret reacting the way we did. Too late.

Another aspect I have considered is that this is preparing me for my eventual release. Things will happen in life that I have no control over, but how will I cope when they do? If I can’t handle being moved to an uncomfortable unit in prison, I am in for a world of hurt when I get out because so much more can and will happen that will upset me. This is a mini-test, and after a week now to reflect, ponder, and respond, I feel I would earn a solid B from my instructor.

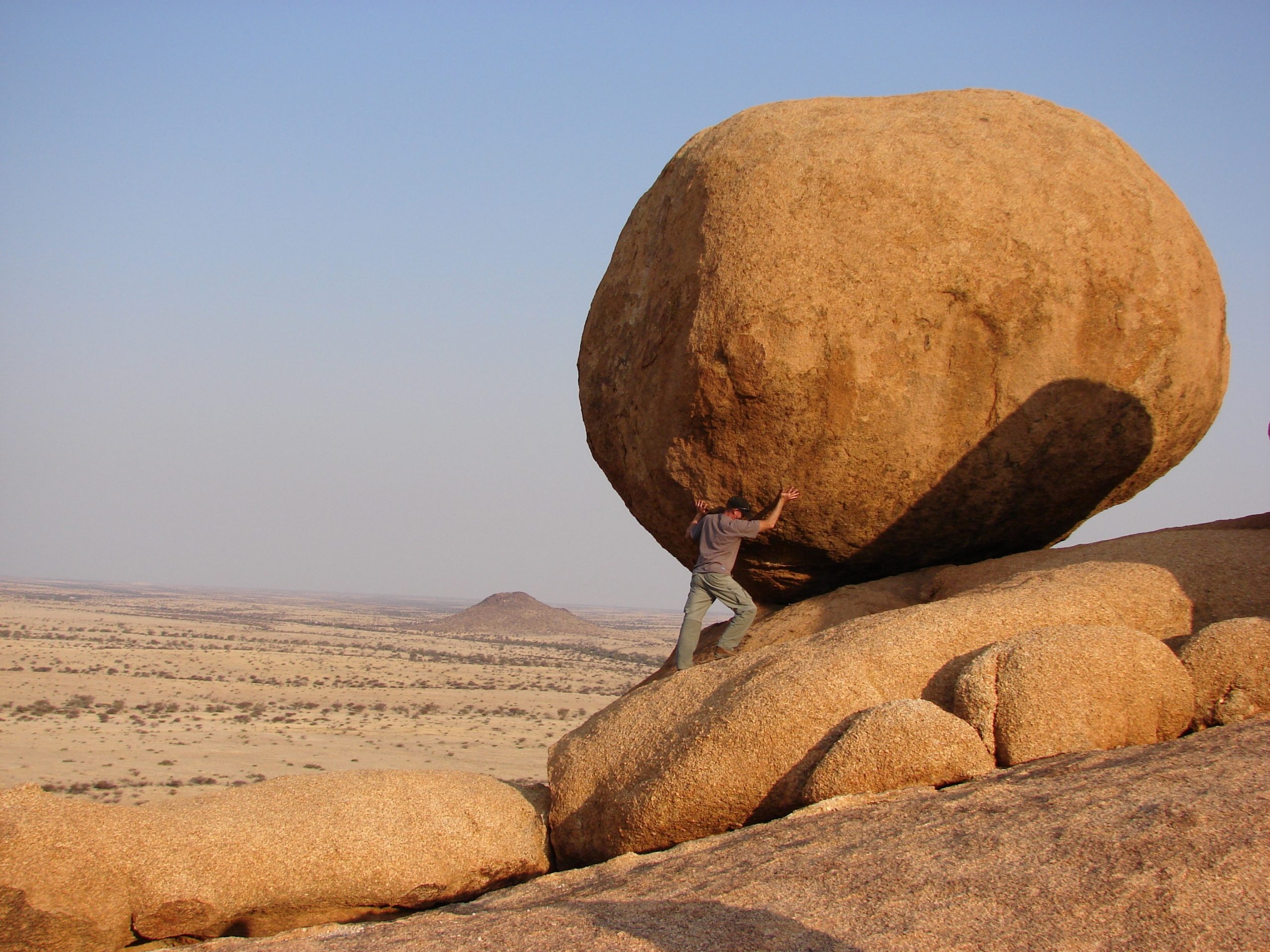

The moral of this short illustration is, we always have a choice in how we respond to life’s unexpected challenges. If we only focus only on the undesirable aspects in front of us, we miss the hidden opportunities to use them for growth in character, and resiliency that can only help us better face other life challenges that will surely come. The goal is, therefore, not to react to negative life challenges but to respond. Responding requires a change in how we view these circumstances in the first place, seeing them as opportunities rather than obstacles.

by Rick Fisk | Jun 6, 2019 | From the Staff

In Finland, they’ve reduced homelessness by 35% because they attacked the problem radically. They tried a little bit of mercy. From the Daily Mall:

“We decided to make the housing unconditional,” says Kaakinen. “To say, look, you don’t need to solve your problems before you get a home. Instead, a home should be the secure foundation that makes it easier to solve your problems.”

With state, municipal and NGO backing, flats were bought, new blocks built and old shelters converted into permanent, comfortable homes – among them the Rukkila homeless hostel in the Helsinki suburb of Malminkartano where Ainesmaa now lives.

They didn’t create a giveaway program. Read the article to find out how they improved the problem. Meanwhile, in LA where they have thrown more money at the problem without considering new ideas, homelessness has risen by 16%.

“The residents are seeing more encampments, more people sleeping on the sidewalks in dirty, unhealthy and heartbreaking conditions,” she said. “They are frustrated by this problem. We need to give people answers.”

Lynn pointed to two vulnerable groups as proof that resources work. Even though nearly 3,000 more veterans were reported homeless last year, there was no noticeable change in the number of homeless veterans on the street. Families experiencing homelessness grew by 8% with nearly 8,000 families being provided homes.

One of the largest increases, however, was among people 18 to 24 years old. Lynn said a 24% jump was partly the result of a change in the methodology of the count. But still, he said, “there was a significant increase, many more unsheltered. We were able to house more youth this year than last year, but this is an overflow population.”

Maybe Los Angeles and other cities should try what is being done in Helsinki, mercy.

by Melissa Bee | May 27, 2019 | From the Staff, News

In a bold move on May 22, 2019, Washington state Governor Jay Inslee expanded an earlier executive order imposing provisions on state agencies, which immigration advocates argued didn’t go far enough. The added provisions make it illegal under state law to comply with federal detainer requests. “Our state agencies are not immigration enforcement agencies,” said Inslee.

This legislation is a declaration that all people are welcome, and that families will be protected from the horrors inherent to the deportation tactics employed by the current administration. As stated on the Governor’s website “I am committed to making sure that every family in Washington state, no matter how they got here, is treated fairly. I want to be clear that we will redouble our efforts to ensure that state agencies are not assisting discriminatory enforcement efforts by federal immigration officials.”

Sadly, for many confined within the Washington state Department of Corrections, the effective date of this sanctuary will come too late.

One such example is a young man named Eleazar Cabrera, who currently has an ICE detainer. Mr. Cabrera (WA DOC #361274) is scheduled for release from Monroe Correctional Complex on May 30, 2019 — a date calculated not based on the expiration of his sentence, but rather, on his good behavior.

His release date comes so soon after the executive order was signed that DOC staff have told him he will still be turned over to INS.

Now 29, he was brought to the U.S. by his mother when he was six, after his father, a police officer in Mexico, was killed in the line of duty. He and his mother were given visas to come to the U.S. due to the threat of violence. His mother (a home-owner in Washington), and one child are his only family — he has no family in Mexico.

To help Mr. Cabrera and others in the same situation, supporters can call and/or email Governor Jay Inslee, Attorney General Bob Ferguson, and the Secretary of WA DOC, Stephen Sinclair with the following message:

Please allow Eleazar Cabrera to waive a portion of his good conduct time, thereby allowing him to remain in prison until after the effective date of the sanctuary state legislation, avoiding automatic deportation to a country he does not know, so that he may safely return to his family.

Governor Jay Inslee

Phone: (360) 902-4111

TTY/TDD call 711 or 1 (800) 833-6388

Online contact form

Atty General Bob Ferguson

Phone: (360) 753-6200

Online contact form

Stephen Sinclair, Secretary

Washington State Department of Corrections

stephen.sinclair@doc.wa.gov

(360) 725-8810