by Rory Andes | Dec 3, 2021 | book review, From the Inside

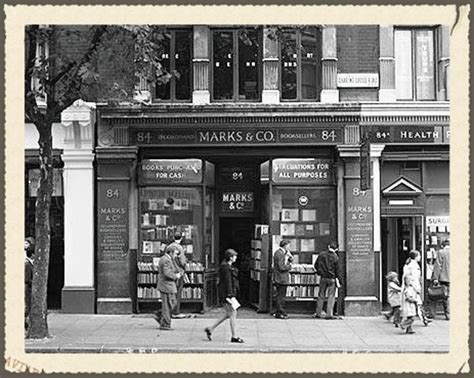

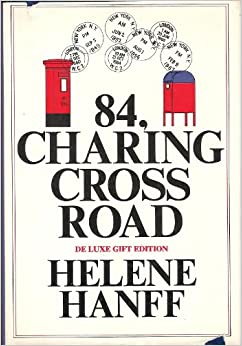

After finishing “84, Charing Cross Road” by Helene Hanff, I couldn’t help but be mesmerized by the power of correspondence. Hanff, through her own personal accounts, shares the ability to know the people you’ve never met. As an incarcerated person myself, most new friendships I strike up with the world beyond are through the power of writing, so Hanff’s ability to befriend a whole bookstore staff on another continent speaks volumes of how powerful written communication truly is.

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…

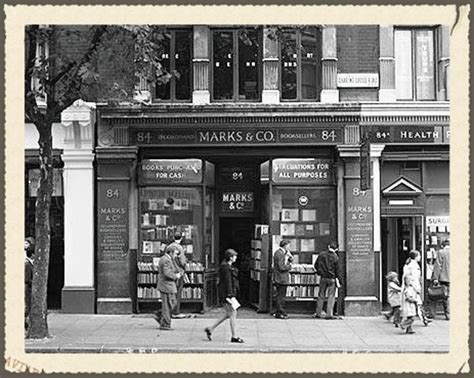

Helene Hanff, a New York writer, takes you on a written relationship with her new friend Frank Doel starting in the fall of 1949. Frank is a shopkeeper for an antique bookstore in post WWII London. Their continued communication is a historical glimpse into how they became decades old friends. Frank and his wife, Nora, along with other workers in the shop like Cecily and Megan, cheerfully struggle with the rationing efforts of a Europe being rebuilt. As a customer, Helene writes often to Frank to get great deals on genuine literary treasures only found in the old world of England and it occurs to her what these people must be going through. She begins to send packages of meats and eggs in a show of solidarity with her new war-torn friends.

84 Charing Cross Road (1987)

Frank ensures that he works diligently at providing her with quality, timeless works and a uniquely British charm. In time, London heals and as Helene’s relationship with Frank and his family ages, Helene gets to become amazingly close with the lives of his wife and children, also. Through the 1950’s and 60’s, Helene keeps a hope that her fortunes will materialize and she could hop a ship to England to visit. As a writer, she lives from one opportunity to the next writing scripts for the newly exploding medium of television. As all things do, there becomes a point in the book where, as a reader, you realize that nothing can last forever. Bad news is conveyed regarding the loss of bookstore’s most knowledgable attendant and condolences are offered through the written word in the most heartfelt and loving manners.

This collection of letters is a short read, but with an extraordinary amount of humanity on every page. I challenge you to not become invested with this stoic cast of characters from a time when society was extremely dignified and cultured, even in its hardships. This book will touch you on a very human level.

*Note from Melissa: This is one of the rare movies that followed the book so closely – much like To Kill A Mockingbird. It is (as of today) available on Amazon Prime Video, and I highly recommend it. If you don’t have Amazon Prime, check your local library for the book and/or movie.

by Rick Fisk | Dec 2, 2021 | From the Staff, Interviews

Photo by Michal Czyz on Unsplash

She-EO, Melissa Schmitt was interviewed by Fern Ridge Community Radio (KOCF) to talk abut Adopt an Inmate, our mission, and some of the issues that people in prison face every day.

by Rick Fisk | Dec 1, 2021 | From the Inside, From the Staff

My name is [redacted], I am 28 years old, I am a father of three, I’m from Odessa Texas and I am currently serving a sentence that I believe I do not deserve.

This is my story.

On August 15, 2018, after I was picked up from a friend’s house, he was taking me back to the place where I was staying. I had been in the car for less than two minutes when my friend turned right and we were stopped and automatically asked to get out of the car. We were initially pulled over for not using the turn signal. Whenever we were searched I had a syringe in my pocket, my co-defendant had a scale in his, which gave rise to the police to search the vehicle, at which point they located a backpack on the passenger seat which I admitted was mine and had a gun. At the time I was traffic-stopped I was not a convicted felon.

I want to declare that I have never been on probation or in any other sentence ordered by a court, however I was out and free on bond for charges that I accumulated in a period of eight months and even then I never signed a document that prohibited me from carrying a weapon as a requirement or stipulation of my bail.

During the search the police found a small amount of marijuana in the center console. I was not aware of the existence of the marijuana or any other narcotic in that car that was unrelated.

After the search was complete, we were taken to the police station for further questioning in which I did not want to speak without an attorney present, thus leading me to federal detention on charges of prohibited person in possession of a firearm while my co-defendant was taken to county jail for marijuana but at the end of the day my co-defendant made it to federal holding stating that the tow truck driver found his drugs under his car and turned it over to the police.

I want to state that this is the first time I had heard of any narcotic being in his possession, those were his belongings in his car and that is why during my judicial process and until the day of the sentence I maintained that I did not know about the existence of those drugs in that car and additionally my co-defendant wrote an affidavit and acknowledged to the courts on record at his sentencing hearing pleading under penalty of purge that I did not know that he had possession of those narcotics in his car and that the drugs were wholly and entirely his property, not mine. It wasn’t until the district attorney maintained that this affidavit was just a piece of paper and the court made my lawyer withdraw from my case that day due to a conflict of interest but when I appointed a new lawyer I pleaded guilty because I was cornered in front of the decision to go to trial, probably lose and get 25 years in prison, or plead guilty and get the mandatory minimum. I was given 2 criminal history points. Both were fines that I never did jail time on and that even with those 2 points my sentence under the sentencing guideline table would have been 78 to 97 months but because of the mandatory minimums I was given 180 months

This is what the criminal justice system generally does, it is an unbreakable institution, that does not admit mistakes, that makes you feel that you will never be able to exercise your right and that you must sometimes even admit something in order not to receive something worse.

While no criminal justice system is entirely perfect, neither is that of the United States. Most people you meet in prison, they come from broken homes, no family ties, so when they come out, they come out with nothing. When these sentences are not only harsh but they are also so long the criminal justice system is only making the fact of rebuilding a life, recovering ties and returning to the free world increasingly difficult, and for many something that never comes.

When you incarcerate an individual, you incarcerate their entire family, and that’s what most people don’t take into consideration. I need to go home sooner for my children, who are the ones for whom I have been keeping it together all these years. The criminal justice system does not take parental relationships into account when sentencing adults. It becomes much harder to maintain a relationship with a parent who is far away and behind bars, and it’s difficult for the parent to take an active role in caretaking.

For ten whole years I did things right. I had a family, a good job, at 23 I bought a house and my children never lacked for anything. I’m ready to do all that again. I’ve done things right for most of my life, but I made the mistake of surrounding myself with the wrong people and doing things wrong for ten months and I’m paying for it.

I have remained quiet and accepted my sentence, but what is fair has to be said. I think I have been wrongly sentenced. I don’t intend to go home tomorrow through the front door, I just want to be heard because I refuse to pay for a crime I did not commit. I want a second chance from someone who can listen to my case. If I am really wrong I will continue to serve my sentence as I have been doing this past few years, but since I know I didn’t commit the crime I am blamed for I feel I really need to be heard one more time.

by Michael Henderson | Nov 23, 2021 | Daily Life in a Florida Prison, From the Inside

Photo by marianne bos on Unsplash

For all the world to see, Hello my fellow travelers in the A.I. Universe, I will be as plain spoken about about the issues concerning incarcerated persons as I can. Sometimes I may have to backtrack to clarify things because this environment gets so damn convoluted it’s hard to follow even from the inside. Convoluted: adj: marked by extreme and often needless or excessive complexity.

No better word exists to describe the daily life of a prisoner. To be fair that there are a number of prisoners who make life difficult for themselves and others. This number is nominal. Some of the idiotic actions by these prisoners are mind blowing. Like stabbing someone because of some perceived disrespect. Just like on the street this behavior should never be tolerated. However when an incident happens in the outside world you don’t punish the whole neighborhood where the offense took place. For some reason this blanket punishment has become a necessary component of a reasonable penological interest. Whatever that means. The only result of this type of mass punishment is that of a negative nature. In all its forms. For instance, the controlling mentality driving daily life is that an officer’s job is to punish the inmates even though the stated duties are care, custody, and control. Nothing more. Not judging a person’s charges and physically abusing them for that which they are being punished for already. Nor keeping them from a job or educational assignment they are eligible for as added restrictions just because an officer has the ”power” to do so.

When there is a physical altercation between two inmates, the entire dormitory is placed on some form of restrictions ie loss of recreation or canteen access. Or as in the events that took place two weeks ago that led to a weeklong lockdown. This brings me full circle to the censored article that I attempted to post two weeks ago. The reason given for the censor was simply ”weapon.” However my reference to the possibility that the phone call alleging the threat may have originated from a phone smuggled into the prison by a staff member is more likely the reason for the censorship. If all of this seems to be arbitrary and capricious from the outside looking in, imagine the sheer chaos that prisoners are forced to live in everyday. And they wonder why the recidivism rate is so high … or do they?

Peace and love. Namaste’.

PS. I never did get my socks back or even my grievance responded to. 🙂

by Inmate Contributor | Nov 20, 2021 | From the Inside

*CHARLES WALTER WEBER JR.*

DOC #772708/C-D01

Clallam Bay Corrections Center

1830 Eagle Crest Way

Clallam Bay, WA. 98326

My Family and Friends,

Thank you to Jules at the Critical Resistance-Portland I have this mission to join and see to the end.

The last piece “Defund DOC and Decarcerate Now!” I posted last year was written to push those Senate and House Bills to be passed. We didn’t get the love we needed to get them all the way through. Not regarding any of the sentencing issues, but I’m writing up a revised piece right now, and next year all of these Bills are going back up to the legislative during sessions. I need my family to push this shit for me and the prisoner population in Washington State:

#1) House Bill 1344 – Requires resentencing for people convicted as emerging adults (under 25 – that’s me)

#2) House Bill 1282 – Restoration of a universal 33% earned time accrual rate (this puts me out on my original case March 30th. 2022)

#3) House Bill1169 – 33% Earned time on enhancements and limiting stacking of enhancement (same as #2 for me)

#4) Senate Bill 5413 – Restrictions on use of Solitary Confinement

#5) House Bill 1413 – No use of juvenile points in adult sentencing (with other bills above puts me out NOW!)

#6) Senate Bill 5036 – Expansion of clemency and extraordinary medical placement

We got some love on education bills, graduated reentry, and voting rights, also the guys struck out on Robbery 2°, so we made some headway, but this coming year we need to push hard. Please vote, petition your legislature, and outside these courthouses and legislative buildings and DOC Headquarters to #FreeThemAll-WA, and join the Critical Resistance-Seattle, because the Resistance IS Critical my Family and Friends. Please get involved, and know that this Revolution to Dismantle, Change, and Rebuild this corrupt money pit called DOC is just getting started.

It’s time to Liberate our country from the 11th, and 13th Amendments.

Dismantle! Change!! Rebuild!!!

Critical Resistance-Seattle

#FreeThemAll-WA

C. Walter Weber

Tiller of the Earth

by Michael Henderson | Nov 19, 2021 | Daily Life in a Florida Prison, From the Inside

Edvard Munch’s iconic painting ‘The Scream’

Hello AI Family,

Have you ever been refused access to use the toilet? I mean without being held in a hostage situation like a bank robbery or a kidnapping. A very rare event. But even victims of those circumstances report receiving these basic humanitarian necessities. But not the victims of the white shirts of the Florida department of corrections.

These ”white shirts” as they are known, are any rank higher than a sergeant. Lieutenant, captain, major, colonel. Objectively, taking into account that there are people in the white shirts, and, at least ostensibly, they have reached a level of reasoning commensurate with the decisions they are required to make in order to maintain an already extremely stressed population of men, some of these folks still haven’t acquired the skill set to rationally make decisions to correct behaviors that are considered incorrect.

A description is needed here. In all prisons there are count times. Generally, the stock in these human warehouses are inventoried around five times during the waking hours of a day. The last waking count is known as a master roster count. We are allotted a ten or so minute regrouping period to retreat to our bunks for the count. This really seems like a never ending process some days. A couple of nights ago there was apparently a staff shortage and the white shirt on duty was in the dorm for count. I’m not sure that this particular night was one that required an extra minute to settle but all of a sudden the white shirt was screaming her lungs out, threatening to ”lock-up” not any offenders of her directives, but the neighbors of said offenders. Now remember that a lot of these men are here because they are unable to follow rules in the first place. So under a storm of vitriolic invectives these men are supposed to police each other. The end result could have very easily been a violent confrontation between any number of men — especially after the white shirt declared that we couldn’t use the toilets. Some tyrannical prison guards inflict this particular brand of power-wielding on their wards — either as in this case punishment for some perceived breach of their authority, or as a standard ‘I can do whatever the hell I want.’ At any rate, it can’t be healthy to keep someone from using the toilet. I would even suggest it falls under cruel and unusual punishment. But what I find even more striking is the perceived need to scream and yell threats of even harsher punishment for simple infractions at men who are already dealing with an almost impossible living condition.

According to the officer’s code of conduct, Fla. Administrative Code CH.33-208, this primitive coercive form of communication is strictly prohibited. As with primarily every other section of this code there is zero accountability. The ”professionals” are not held to their own standards of conduct, and yet, the wards are held to a heightened standard of not only their own conduct, but apparently the next man’s conduct as well.

The questions remain the same, ”Do you want your neighborhoods, your families and your loved ones to be safer? Do you want your incarcerated family and loved ones to reenter society better equipped to be a productive member of your community?” Our current modality of incarceration and non-accountability of the incarcerator will never achieve correction.

Much peace and love

Namaste’

by Rory Andes | Nov 14, 2021 | From the Inside

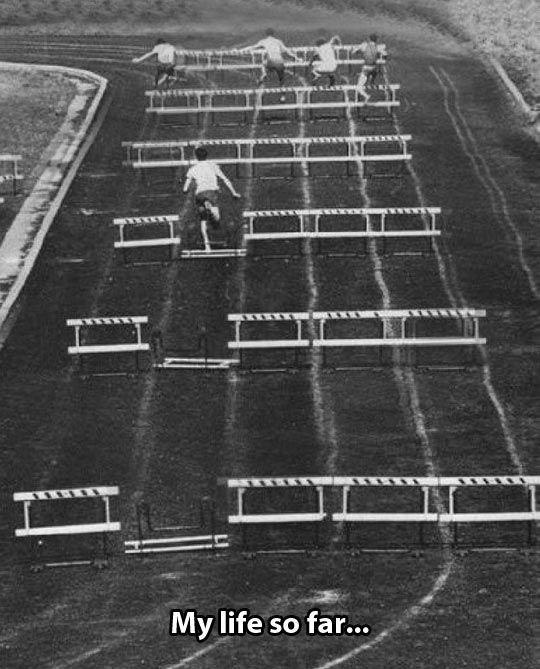

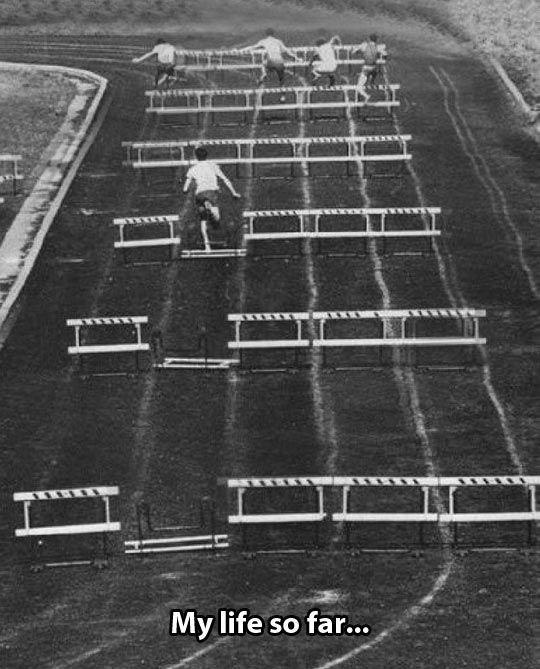

I recently read a book by Ryan Holiday titled The Obstacle is the Way, where he really digs into stoicism and how to bravely face adversity, a struggle, and use it to create something more. One chapter that struck me talked about “love everything.” I really had to sit on that. Love everything. Don’t bear with it, certainly don’t hide it or from it, just love it, whatever “it” is. How do I love the things chipping away at me currently? Of course I love the friends I have and the successes I find. I love my connections to the free world. I love that how I lead my personal life means so much more to me now than it probably has at any other point in my history. I work hard and I feel like I flourish in the hard work. I deeply love that. But prison? How do I love the obstacle of prison? Well, I can love knowing that, as pompous as it sounds and I don’t like that part of it, I’m not like the people who flourish in criminality (like, I get it… I’m IN a prison for reasons other than being saintly). But, I love the rebirth of my values, personal standards, and the emotional healing that emerged in prison. I love being able to foster extraordinary relationships with like minded people and I know I AM the company I keep, especially in a place like this. I can also love that I’m far closer to the end this sentence than the beginning. In the home stretch! I can love that! I love that someone gave me a voice to tell an audience these things from behind walls and I love the book-worthy situations I’ve found myself in, all while being sequestered from society. I love how I’ve grown and into whom here. And I love that throughout this prison time, I’m ok with being flawed, because it made me better. I’m human and I have setbacks from time to time, but it’s in those obstacles that I find things to love…

Of course, this is just one small aspect of this book. Leaning forward into the obstacles is the theme. Make them count. Make them memorable. Let them lead the way to success. From Thomas Edison, to Ulysses Grant, to Marcus Aurelius… all leaders of historical measure who knew how to use adversities as guideposts. But importantly, for me, the idea of love is what resonates the most. That’s something I can truly get behind…

by Martin Lockett | Nov 14, 2021 | From the Staff

Note from the staff:

We started this organization in an effort to help inmates and expose the public, one connection at a time, to the current state of our justice system. We also want adopters to have every tool to help their friends on the inside. Harm Reduction is a big part of this.

Many of our followers have enjoyed blog posts written by our dear friend Martin Lockett. We are happy to announce that Martin completed his 17 1/2 year sentence and walked into freedom in June of this year. We were able to attend his first public speaking event in Eugene, Oregon in August shortly after his release, and are looking forward to another chance to hear him speak this month in Salem, Oregon. He’s employed as a Certified Alcohol and Drug Counselor, and brings a wealth of knowledge and experience to his clients. Martin is available for public speaking engagements, and you can read more about him on his website MartinLocket.com.

We’ve asked Martin to write about Harm Reduction for our readers. Specifically:

- What is it?

- Why is it important?

- How can you apply it to your adoptee (or anyone)?

The term Harm Reduction is well known within the substance abuse treatment community and is one that has caused much controversy. It is not well known to many in the general public, but it should be. Allow me to explain what Harm Reduction is.

Harm reduction (HR) is a philosophy that promotes human rights and equal justice. It focuses on positive changes people make while in the throes of their addiction. It is predicated on meeting people where they are to reduce harmful consequences of their use, but doing so with compassion and dignity. Harm reduction runs counter to the often-seen model of total abstinence because HR places an emphasis on mitigating one’s harm to self through drug/alcohol use while total abstinence punishes use. Harm reduction seeks to improve the life of the person by empowering them to make safer choices in their use and leans on them for ideas of how they can best be served.

For instance, say you encounter someone who is addicted to meth, and he uses it intravenously. He often uses with other friends, and they share needles. He works a job and finds that his use makes him underperform at his duties because he doesn’t get proper sleep. He has come to a treatment program and wants to quit using but doesn’t think he can – at least at this moment. But he knows the way he uses (sharing needles) is not good and wants help with that. Many programs would require he abstain entirely to stay in their program, but a harm reduction approach is going to meet him where he is, understand that he has goals for his life and his use, and any reduction to the harm he is putting himself in is considered a success.

At this point, a treatment plan for this client could be drawn up to include getting him enrolled in a needle-exchange program, eating square meals daily, and going to bed by a certain time. It would be understood that this client would still use meth during this time, but over time, as he adjusts to using more safely, the focus could then be to revisit his initial goal of abstaining. If this is still his goal, then that would be the aim; if is it not, then that is acceptable as well. The goal is to always reduce the harm caused by using and increase the quality of life of the client. Working with this client to improve other areas of his life would be the next goal. The client would direct his treatment plan and the goals of his life. Again, a much different approach than an abstinence-based treatment program.

This approach is important because it affords people dignity and autonomy in how their lives will be lived. It empowers one to make choices that will improve their life, which, over time, will enable them to continue to make good decisions and reap the benefit of them. They may reach a point where they can see how not using substances at all would be beneficial, but again, this is not for anyone else to decide for them. Treating human beings as independent thinkers and stewards of their own lives is what we all desire. Not being subjected to others’ judgement is what we all desire – this approach affords that. When abstinence-based approaches operate from a punitive standpoint (when someone relapses while in their program), it shames the client and makes him/her feel they are a failure who is not deserving of forgiveness. After all, they have encountered this from many in their families and friend circles for years. This ostracization is only reinforced when chastised through an abstinence-based program that allows no room for error. Now, let’s look at how the HR approach can be applied to Adopt an Inmate and how it can be applied.

Many who are incarcerated have not been met with compassion, understanding, non-judgement, autonomy, and justice. These may sound like basic offerings humans offer one another, but they are not, particularly for those who have found themselves mired in a life of addiction and incarceration. These principles can be displayed by you, the adopter, through simple measures and gestures.

- Writing letters of encouragement

- Sending educational books/material

- Accepting phone calls/video visits (at whatever degree you’re comfortable with)

- Connecting inmates with resources in their community upon release

- Exploring with inmates what they are passionate about and reaffirming their ability to

do be successful

- Helping find and send internet material that is conducive to meeting their goals

- Sending holiday/birthday cards

These are examples of just a few ways to display a harm reduction approach toward your adoptee but believe me when I say they go a long way. It conveys a powerful message that someone cares and wants to support me – which is reason enough for me to begin to believe in myself and want better for my life. You can decide with your adoptee what will work best in terms of support, but you understand the goal of this approach and how you can help change someone’s life in a meaningful way. It does not focus on what got the person in prison or condemning their behavior through a program that gets them to confess every bad thing they’ve ever done; it meets them where they are and allows them to focus on becoming more responsible for their lives and how they want to live it going forward. And make no mistake, this mentorship dynamic is mutual – you will most certainly be enriched and educated along the way. Humanity is made better when we all help each other and learn from one another.

by Michael Henderson | Nov 13, 2021 | Uncategorized

In a real world of problems and solutions it is generally practiced to recognize where a problem exists and to seek a resolution to the problem. Enter the incredibly inaptly named world of the Florida Department Of Corrections. The misnomer doesn’t only stem from the fact that there is absolutely zero correcting the behaviors of the wards of the state, but also it stems from the need to acknowledge the department’s inherently flawed inabilities to police itself and seek solutions to the problems that come from a need to cover up the behaviors of the very people charged with correcting the behaviors of the wards of the state.

Let me see if I can un-convolute this for you with a couple of situations.

The process for a prisoner to redress a problem is known as the ”grievance process.’ In Florida this is a three step process that must be completed before a person in prison can exercise his constitutional right to seek redress from the courts. Thanks be to the U.S. Supreme Court for consistently viewing prisoners as less than human. No matter, the grievance process simply doesn’t work anyway. Knowing this, I use this process only to bring attention to the problems that are rampant with the people who run this show. It is decidedly so that the system will spend a million dollars to save a dime.

This brings me back to the great sock caper. If you remember a couple of weeks ago I reported that the top ranking officer at dormitory inspection essentially helped himself to socks that I had in of all places… my laundry bag. For reasons unknown, the major emptied my laundry bag onto the middle of my bunk and made away with another mesh bag we use for canteen shopping that I had meant to throw away, and three brand new pairs of socks. I received a property form for the canteen bag but alas not the socks. The following is a verbatim copy of the grievance that followed and the response.

This informal grievance is in accord with F.A.C. CH 33-103.001(1)(2)(4), 33-103.002, 33-103.005, 33-103.010, 33-103.011, 33-103.014. On Feb 10 20211 during dorm inspection Major Crawford emptied my laundry bag onto my bunk. For whatever reason the major confiscated a trashed canteen bag and three brand new pairs of quarterly order socks with gray toe and heel. If these socks were taken because there were other socks, those were all the state socks with holes that I could not get replaced from laundry. Hence my family had to purchase those socks. The major could have taken the state socks. Later that evening Sgt Cooper brought to me a property slip for only the canteen bag. He knew nothing about the socks. It will be evident on camera that Major Crawford left with the socks and most of the dorm witnessed him with the socks. The remedy sought is to return the 3 pairs of brand new quarterly order socks or apply to risk management for a refund of the amount of purchase as per F.A.C. ch. 33-602.201(14)(a thru e).

(Response from someone named Washington): Informal is vague and cannot be clearly investigated. You’ve failed to provide the time of this incident therefore video cannot be reviewed.

This is a tactic frequently employed by the department of corruption in order to avoid owning up to the completely flawed system that allows for the lack of professionalism and the recycling of criminal behaviors that fuels recidivism and mass incarceration. Never mind that dorm inspection is every Wednesday at approximately the same time. Defend and deflect.

Again, do you want your cities to be safer? Do you want your incarcerated loved ones to become productive members of society? We have to have professionals who act professionally. We have to make punishment subordinate to rehabilitation. And we must acknowledge the inherent and problematic methodology of penology that is more akin to Abu Grab than the treatment of our own citizens.

The only real effect the flagrant lies spewed onto the grievance response served was to piss me off. My only recourse is to continue the grievance process with an appeal to the creators of the mess in Tallahassee at the head office, which will invariably be denied thru either the same or some other contrived nonsensical reasoning, then go on to file a small claims court suit in which FDC will spend copious amounts of money to not admit that the offending employee was in fact wrong, also requiring them to replace six dollars worth of socks. Obviously a route 99.99% of inmates are not willing to travel. So with the blessing of the dysfunctionality of a system designed to not only allow, but to perpetuate itself thru the permissible subterfuge of supposedly keeping the public safe, men and women are abused, sometimes to death, women are impregnated, and even juveniles suffer atrocities at the hands of so-called professionals and all are left with a method of redress known as ” the grievance process” that is not just simply ignored, but actively thwarted by it’s inherent design. If all you show a man is corrupt methods of existence, in order to sustain the same system that calls itself the department of corrections, that’s all a man will learn. Dysfunctional corruption. Teach a man to fish.

This picture I’m painting is as representative as I believe anyone could paint no matter how outlandish it may appear. There is absolutely nothing rehabilitative about the penology employed by the Florida department of corrections. As I suspect is true in other departments throughout the U.S. as well rendering the rate of return to prison commensurate with the need for jobs to stir the economy in a state that depends on being pretty to sustain the lavish lifestyle of the few.

We’ve yet to discuss the nonexistent medical care in the Fla. department of corruptions, a subject that will I think require an installment all its own.

On a final note, I’m no longer at Columbia correctional, I’ve been transferred to Lake correctional, an institution purportedly scheduled to be torn down. Your guess is as good as mine. The topic shall be commented on in future postings.

Until then, much peace and love. Namaste.

by Rory Andes | Nov 3, 2021 | From the Inside

Everyone knows of him. He’s the guy with the white beard. He’s in his late 50’s and still manages a pony tail that he can braid. Some guys are envious of his hair. He carries a comb in his back pocket like a kid from last century. He talks about his mom like she’s his best friend. She comes and visits almost every week, you know, just ask him. When he tells it, she’s his only friend.

Life has escaped him, forgotten him, but he tells himself it’s ok. He still has his mom’s kind love. But from time to time, he stresses about her health. He knows she won’t live forever. Then what? Who will care, then? His appeal to the court should come through any day now, then he can help take care of Momma. Lord knows she could use the help at her age. Those sharp attorneys just about have his final sentencing argument ready, from his understanding. Then he’s getting some of that time back. It’ll be over with for this separation from Momma. She really needs his help.

He’s been in prison almost 40 years for a vicious rape that happened after a hard night of drinking. He can’t begin to remember who she was or what even happened. All he knows of her young face are the brutal photos the police took. All he knows of how it happened was that they knew a few of the same people at the same party and he came on to her. He has no idea how or why things escalated to such an event. Not really. He was way too trashed that night. His memories don’t exist. All his information of what happened came from police reports he couldn’t read until months later, before his trial.

What he does know is she’s a success. She has been for a long time now. His momma told him that at some point. She graduated college, married a banker and has four kids that make it home for the holidays. He’s glad she turned out ok. He’s glad he didn’t go so far that he ended her life. He just doesn’t know why he hurt her or how he got to where he went with it, so violent and not himself. In the moment, he wasn’t what Momma raised. What he does know is he did something awful to that young lady. He also knows that she hurts somewhere inside today because of him. He still doesn’t know how to reconcile with himself or how to feel about himself over it.

It’s that time of day again. He has to get in line for the phone. He has his notebook ready in case the paralegal has any new information for him. The laws about sentencing change all the time and people get some time back for those court rule changes. It’s his turn, now. He dials the phone and waits. No answer today. Man, he was hoping he could talk to the paralegal today. He knows how busy his lawyer is, too. Momma needs him to have good news, though.

The sad fact is, the paralegal doesn’t answer because the lawyer working on his appeal hasn’t been in practice in over ten years now. All of his appeals had been exhausted decades ago. His 53 year sentence still stands. He stays hopeful for that appeal because he’s broken. He’s certain that he’ll help his mom soon because he’s broken. His life has escaped him because he’s broken. Maybe he crossed that line a long time ago because he was broken then, too.

In reality, Momma has been gone for a few years now, too. It was heartbreaking for us to see him fall apart when the prison chaplain told him. He’s paid quite a price for being this broken. He committed a crime he never could remember, and remembers things that quit happening so long ago. His mind has disengaged from reality years back and now it’s like this for the sake of his own salvation. He might live to see freedom someday, but probably not. No one would care anymore, anyway. All because he’s broken…

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…