by Rory Andes | Jan 4, 2022 | Uncategorized

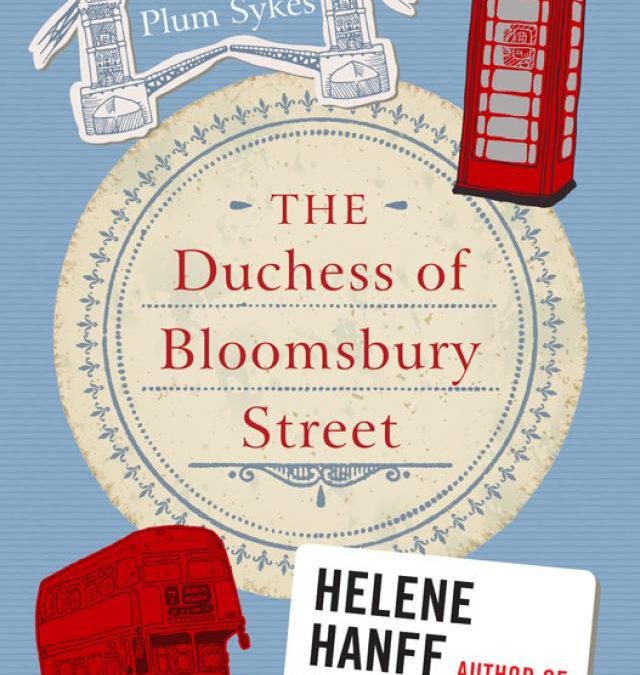

In her follow up volume to “84, Charing Cross Road“, Hanff takes you on a ride through her adventures in London in “The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street.” After 20 years of corresponding with the Doel family and a burning desire to visit London, Hanff finally cashes in on her worldwide popularity with the publication of “84” and, at age 55 in 1971, decides to walk the streets of a city that was the source of her fantasies… and success.

Following some similar formats in the way of letters, Hanff captures her trip in a journal encased in amazingly detailed descriptions of London’s citywide layout. Personally, as I read this, I wish I had an atlas or Google Maps to virtually share her travels. Helene Hanff has a very distinct personality of an American from New York and her neurotic behavior is cleverly comical as she attends book tour commitments throughout London. With new characters like the Colonel (someone who might be described as a groupie, or a stalker) and the management team of her London based publisher Andre Deutsch who wrangle her through her tour, you also get to meet, as Hanff did, Nora and Sheila Doel… the family of Frank Doel, who was the other half of Helene’s charming 20-year-long letter communications to London’s Marks and Co. Booksellers in “84”.

This follow up has much of the same charm and character as its predecessor and, as before, it showcases a wonderful older generation of class and style with it. Hanff’s encounters with the British lifestyle she’s always envisioned are endearing and highlights what expectations do to someone who takes on her dreams in midlife. A fun and heartwarming ride with Helene through London in the 70s will make you often laugh. While it could be read on its own, I highly encourage reading “84, Charing Cross Road” to truly appreciate all that went into the need for this follow up book. If you like the storytelling of folks like Nora Ephron, you’ll love Helene Hanff.

by Jacob (Justin) Gamet | Dec 31, 2021 | Uncategorized

Photo by kalei peek on Unsplash

We don’t see things the way they are.

We see them the way we are.

— The Talmud

Most teenagers can’t wait to turn 18, a time marked by the independence (and adventure) of them moving out on their own, embarking on their dreams via college or serving their country, or the mere prospect of forming new relationships. However you slice it, it’s when youthful adults venture out into Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) to come into their own.

So tell me, when you were younger, did you ever like a guy or girl, a food, or anything, and as time passed, you stopped liking him or her or it? It’s like you “aged out” of who or what you were previously enamored with or entranced by. I mean, I used to enjoy hanging out with certain types of people, and now I avoid them like COVID-19. Unless they’re doing something positive, I classify such types as “Hi and Bye” acquaintances, whom I spend as little time as possible with.

For example, I have some past “so-called” friends who believe I’ll get out and smoothly segue back into our youthful pastime activities without missing a beat. Some even say, “Jay ain’t changed.” Hmm, that’s naive and mildly disturbing given that I will have spent “18 and change” (i.e., over 18 years) in prison, and they expect me to leave prison as the same person I came to prison as?! Although, and most unfortunately, there are some guys who press the psychological and behavioral pause button upon entering prison, and re-press it when they release, I’m definitely not one of them.

Contrary to prevailing frenemy belief, prison turned my life upside down, which as I later discovered was actually right side up. I came to prison because my upside-down outlook on life skewed my perception of reality. Paraphrasing my opening quote, the world did not change, rather, only my perception of it did.

I’ve spent years trying to figure out where I went wrong, and the further back I looked the closer I got to the answers. Pre-prison, I was living my life through my tattered past. As Dr. Phil said, “The past reaches into the present, and programs the future, your recollections and your internal rhetoric about what you perceived to have happened to you.” I learned that I was living my adult life through the tragedies of my negative social environment growing up.

And since my formerly-flawed thinking produced criminal behavior that, in turn, resulted in me having to serve 18 and change in prison, I’m often overtaken with residual guilt, shame and remorse. It’s like a web that wraps you tightly, squeezing tighter and tighter with an endless thread. Don Miguel Ruiz explains this in The Four Agreements:

How many times do we pay for one mistake? The answer is thousands of times. The human is the only animal on earth that pays a thousand times for the same mistake. The rest of the animals pay once for every mistake they make. But not us. We have a powerful memory. We make a mistake, we judge ourselves, we find ourselves guilty, and punish ourselves…. Every time we remember, we judge ourselves again, we are guilty again, and we punish ourselves again, and again, and again.

And then there are those in society who seek to tighten the web even more by reminding you of your past mistake at every corner — without considering the mitigating factors that contributed to your downfall — pushing you to relive the past on an endless loop. They forget that every saint has a past, and every sinner a future. They judge with four fingers pointing back at them. They demand retribution, but when they (or their loved ones) are standing in the shoes of the accused, they beg for mercy and leniency.

But the good thing is: I’ve incubated for years in this concrete cocoon and improved myself in ways that the majority in society cannot because they haven’t walked my Road to Redemption, where I’ve had to revamp and reinvent myself and overwrite my faulty thought processes with success-oriented programming. Every day I use my 18 and change to update my life outlook and further disentangle myself from the web of guilt and shame.

I approach each new year as an exciting new chapter in my life, as one of many phases of my metamorphosis. I am a new creation, a phoenix risen from the ashes, a butterfly ready to explore and perceive the same world (i.e., minus the landscaping of technological innovation) through a different, more colorful lens.

And if ever accused of being the same person I was when I committed my crime, I would simply reply, “True, I am the same essence. But in terms of form, I have changed by leaps and bounds and become someone exceedingly better.” Therefore, my world has changed — but only on account of my perception changing over the course of my 18 and change.

As you embark on the new year and hope to improve some aspect(s) of your life, I want to give you a handful of positive affirmations for 2021 (in the era of COVID-19) from my affirmation stockpile that has helped me develop the right attitude to overcome WHATEVER life throws at me.

God willing, I’ll be released in 2022! Happy New Year!

#ReadChangeLiveChangeBeChange

==============================

Positive Affirmations for 2022

==============================

We have to be greater than what we suffer.

–Spiderman, movie

The world is hard. You have to be harder.

–Unknown

You gotta do what’s best for you with the time that you got.

–Detective Pikachu, movie

I am the captain of my ship, and the master of my fate.

–Dr. Ivan Joseph

Fall seven times stand up eight.

–Japanese proverb

Sometimes, the only way to heal our wounds is

to make peace with the demons who created them.

–Godzilla II: King of the Monsters, movie

Sometimes we’re tested not to show our weaknesses,

but to discover our strengths.

–Unknown

The darkest nights produce the brightest stars.

–Bumblebee, movie

by Rory Andes | Dec 8, 2021 | From the Inside

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

He knew it was deep. He felt the blade push against his body and knock him off center. And another one. And another. Fifteen times as he tried to get out of the grasp of the two guys holding him. He felt no pain though. All he could feel is the warmth of his blood soaking into his clothes. As his assailants were shot at from the guard tower, Inmate 15422 fell to the ground to dodge the bullets. The sting of pepper spray from the rushing guards started to cloud his vision. He looked at his shirt through the tears and realized his panic at the blood rushing from the holes in his clothing. “Why did these two guys do this?” he asked himself. “Who the hell are they?” And just as soon as it happened, they were gone. The guards fought his hands from the wounds and rolled him on his stomach to cuff him. He could feel the stickiness of the blood that was now pooling and twinges of sharp pains started to creep in. As he was pinned down awaiting medical response, he could feel the cold setting over him. For the first time in his life, he knew real danger and feared for his life. He was the guy who got stabbed in the prison yard for reasons he may never know.

In the rush to move him to the prison’s medical unit, he felt his panic fade. The light became both brighter and more narrow. Being moved down the hall, he started to close his eyes. The life was leaving him and, for the briefest of moments, he examined what tomorrow would bring.

Tomorrow, he would see his mom. He hasn’t seen her in years. She was the rock of the family and took care of him and his two brothers after dad was killed in that car accident. Tomorrow, he’d see dad, too. Mom had been gone for almost 20 years now after the cancer took her. His oldest brother Tim should be there, too. Timmy died of alcoholism a decade ago. Life’s traumas were a lot for Tim and he needed an escape. He found it in the bottom of a bottle when his wife left him. Aunt Claire should be there tomorrow, too. Mom’s favorite sister became his favorite aunt. Claire had that about her, just a spark plug. She passed of heart disease, the family curse, shortly after mom. Then there was Kevin, the neighbor kid who would become his best friend in high school. Kevin enlisted in the Marines and was killed in desert conflict a few years after graduation. Kevin’s family was crushed, but damn, it would be good to see him again. Then it was difficult to recall anyone else. It was difficult to inhale. The cold grew comforting and the peace very embracing. Yeah, he’s gonna see a lot of people tomorrow. He just wishes he could see one last one today. She made his whole world bright and he was gonna walk off this prison sentence and make up lots of time with her. He owed her that, but it seems he’ll be her tomorrow someday…

He felt the warm sun shine on his face as the world became alive again. He was laying in a hospital bed, the curtains parted to let in the light from outside. He realized he wasn’t dead from a prison yard stabbing. The rest of the family will have to wait for him. Each tomorrow led to another one, day by day, until the end of his sentence. Then that tomorrow brought him his release date. He owed his daughter Donna a lot of tomorrows. She was that brightness he was looking forward to. He cried when he hugged her for the first time since she was eight. He saw how the tomorrows piled up and made his daughter into a woman, a mother, with her own family. As they drove down the road, he realized that being temped by any part of tomorrow was a peaceful thing. There are things to look forward to in all of his tomorrows. Tomorrow brought him from Inmate 15422, back to being plain ol’ Danny again. Come life or death, tomorrow has so much in store for him. From being a grandfather, to being a son, he’ll stay just a bit tempted by the taste of tomorrow…

by Rory Andes | Dec 3, 2021 | book review, From the Inside

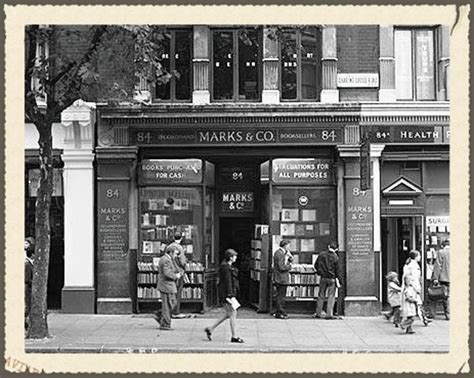

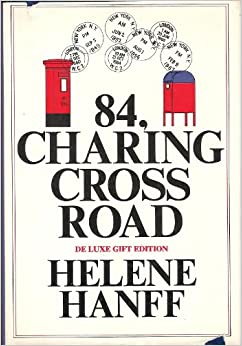

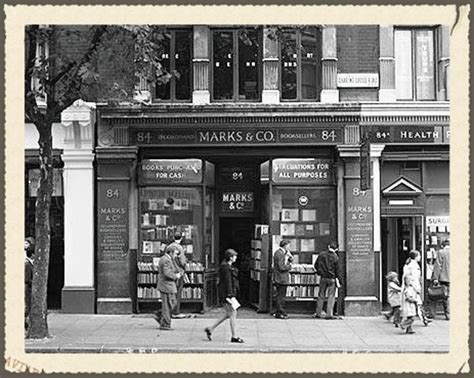

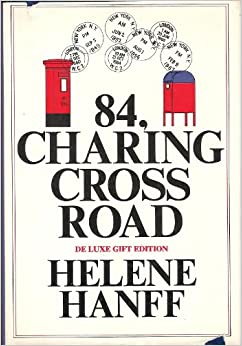

After finishing “84, Charing Cross Road” by Helene Hanff, I couldn’t help but be mesmerized by the power of correspondence. Hanff, through her own personal accounts, shares the ability to know the people you’ve never met. As an incarcerated person myself, most new friendships I strike up with the world beyond are through the power of writing, so Hanff’s ability to befriend a whole bookstore staff on another continent speaks volumes of how powerful written communication truly is.

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…

Helene Hanff, a New York writer, takes you on a written relationship with her new friend Frank Doel starting in the fall of 1949. Frank is a shopkeeper for an antique bookstore in post WWII London. Their continued communication is a historical glimpse into how they became decades old friends. Frank and his wife, Nora, along with other workers in the shop like Cecily and Megan, cheerfully struggle with the rationing efforts of a Europe being rebuilt. As a customer, Helene writes often to Frank to get great deals on genuine literary treasures only found in the old world of England and it occurs to her what these people must be going through. She begins to send packages of meats and eggs in a show of solidarity with her new war-torn friends.

84 Charing Cross Road (1987)

Frank ensures that he works diligently at providing her with quality, timeless works and a uniquely British charm. In time, London heals and as Helene’s relationship with Frank and his family ages, Helene gets to become amazingly close with the lives of his wife and children, also. Through the 1950’s and 60’s, Helene keeps a hope that her fortunes will materialize and she could hop a ship to England to visit. As a writer, she lives from one opportunity to the next writing scripts for the newly exploding medium of television. As all things do, there becomes a point in the book where, as a reader, you realize that nothing can last forever. Bad news is conveyed regarding the loss of bookstore’s most knowledgable attendant and condolences are offered through the written word in the most heartfelt and loving manners.

This collection of letters is a short read, but with an extraordinary amount of humanity on every page. I challenge you to not become invested with this stoic cast of characters from a time when society was extremely dignified and cultured, even in its hardships. This book will touch you on a very human level.

*Note from Melissa: This is one of the rare movies that followed the book so closely – much like To Kill A Mockingbird. It is (as of today) available on Amazon Prime Video, and I highly recommend it. If you don’t have Amazon Prime, check your local library for the book and/or movie.

by Rick Fisk | Dec 2, 2021 | From the Staff, Interviews

Photo by Michal Czyz on Unsplash

She-EO, Melissa Schmitt was interviewed by Fern Ridge Community Radio (KOCF) to talk abut Adopt an Inmate, our mission, and some of the issues that people in prison face every day.

by Rick Fisk | Dec 1, 2021 | From the Inside, From the Staff

My name is [redacted], I am 28 years old, I am a father of three, I’m from Odessa Texas and I am currently serving a sentence that I believe I do not deserve.

This is my story.

On August 15, 2018, after I was picked up from a friend’s house, he was taking me back to the place where I was staying. I had been in the car for less than two minutes when my friend turned right and we were stopped and automatically asked to get out of the car. We were initially pulled over for not using the turn signal. Whenever we were searched I had a syringe in my pocket, my co-defendant had a scale in his, which gave rise to the police to search the vehicle, at which point they located a backpack on the passenger seat which I admitted was mine and had a gun. At the time I was traffic-stopped I was not a convicted felon.

I want to declare that I have never been on probation or in any other sentence ordered by a court, however I was out and free on bond for charges that I accumulated in a period of eight months and even then I never signed a document that prohibited me from carrying a weapon as a requirement or stipulation of my bail.

During the search the police found a small amount of marijuana in the center console. I was not aware of the existence of the marijuana or any other narcotic in that car that was unrelated.

After the search was complete, we were taken to the police station for further questioning in which I did not want to speak without an attorney present, thus leading me to federal detention on charges of prohibited person in possession of a firearm while my co-defendant was taken to county jail for marijuana but at the end of the day my co-defendant made it to federal holding stating that the tow truck driver found his drugs under his car and turned it over to the police.

I want to state that this is the first time I had heard of any narcotic being in his possession, those were his belongings in his car and that is why during my judicial process and until the day of the sentence I maintained that I did not know about the existence of those drugs in that car and additionally my co-defendant wrote an affidavit and acknowledged to the courts on record at his sentencing hearing pleading under penalty of purge that I did not know that he had possession of those narcotics in his car and that the drugs were wholly and entirely his property, not mine. It wasn’t until the district attorney maintained that this affidavit was just a piece of paper and the court made my lawyer withdraw from my case that day due to a conflict of interest but when I appointed a new lawyer I pleaded guilty because I was cornered in front of the decision to go to trial, probably lose and get 25 years in prison, or plead guilty and get the mandatory minimum. I was given 2 criminal history points. Both were fines that I never did jail time on and that even with those 2 points my sentence under the sentencing guideline table would have been 78 to 97 months but because of the mandatory minimums I was given 180 months

This is what the criminal justice system generally does, it is an unbreakable institution, that does not admit mistakes, that makes you feel that you will never be able to exercise your right and that you must sometimes even admit something in order not to receive something worse.

While no criminal justice system is entirely perfect, neither is that of the United States. Most people you meet in prison, they come from broken homes, no family ties, so when they come out, they come out with nothing. When these sentences are not only harsh but they are also so long the criminal justice system is only making the fact of rebuilding a life, recovering ties and returning to the free world increasingly difficult, and for many something that never comes.

When you incarcerate an individual, you incarcerate their entire family, and that’s what most people don’t take into consideration. I need to go home sooner for my children, who are the ones for whom I have been keeping it together all these years. The criminal justice system does not take parental relationships into account when sentencing adults. It becomes much harder to maintain a relationship with a parent who is far away and behind bars, and it’s difficult for the parent to take an active role in caretaking.

For ten whole years I did things right. I had a family, a good job, at 23 I bought a house and my children never lacked for anything. I’m ready to do all that again. I’ve done things right for most of my life, but I made the mistake of surrounding myself with the wrong people and doing things wrong for ten months and I’m paying for it.

I have remained quiet and accepted my sentence, but what is fair has to be said. I think I have been wrongly sentenced. I don’t intend to go home tomorrow through the front door, I just want to be heard because I refuse to pay for a crime I did not commit. I want a second chance from someone who can listen to my case. If I am really wrong I will continue to serve my sentence as I have been doing this past few years, but since I know I didn’t commit the crime I am blamed for I feel I really need to be heard one more time.

by Michael Henderson | Nov 23, 2021 | Daily Life in a Florida Prison, From the Inside

Photo by marianne bos on Unsplash

For all the world to see, Hello my fellow travelers in the A.I. Universe, I will be as plain spoken about about the issues concerning incarcerated persons as I can. Sometimes I may have to backtrack to clarify things because this environment gets so damn convoluted it’s hard to follow even from the inside. Convoluted: adj: marked by extreme and often needless or excessive complexity.

No better word exists to describe the daily life of a prisoner. To be fair that there are a number of prisoners who make life difficult for themselves and others. This number is nominal. Some of the idiotic actions by these prisoners are mind blowing. Like stabbing someone because of some perceived disrespect. Just like on the street this behavior should never be tolerated. However when an incident happens in the outside world you don’t punish the whole neighborhood where the offense took place. For some reason this blanket punishment has become a necessary component of a reasonable penological interest. Whatever that means. The only result of this type of mass punishment is that of a negative nature. In all its forms. For instance, the controlling mentality driving daily life is that an officer’s job is to punish the inmates even though the stated duties are care, custody, and control. Nothing more. Not judging a person’s charges and physically abusing them for that which they are being punished for already. Nor keeping them from a job or educational assignment they are eligible for as added restrictions just because an officer has the ”power” to do so.

When there is a physical altercation between two inmates, the entire dormitory is placed on some form of restrictions ie loss of recreation or canteen access. Or as in the events that took place two weeks ago that led to a weeklong lockdown. This brings me full circle to the censored article that I attempted to post two weeks ago. The reason given for the censor was simply ”weapon.” However my reference to the possibility that the phone call alleging the threat may have originated from a phone smuggled into the prison by a staff member is more likely the reason for the censorship. If all of this seems to be arbitrary and capricious from the outside looking in, imagine the sheer chaos that prisoners are forced to live in everyday. And they wonder why the recidivism rate is so high … or do they?

Peace and love. Namaste’.

PS. I never did get my socks back or even my grievance responded to. 🙂

by Inmate Contributor | Nov 20, 2021 | From the Inside

*CHARLES WALTER WEBER JR.*

DOC #772708/C-D01

Clallam Bay Corrections Center

1830 Eagle Crest Way

Clallam Bay, WA. 98326

My Family and Friends,

Thank you to Jules at the Critical Resistance-Portland I have this mission to join and see to the end.

The last piece “Defund DOC and Decarcerate Now!” I posted last year was written to push those Senate and House Bills to be passed. We didn’t get the love we needed to get them all the way through. Not regarding any of the sentencing issues, but I’m writing up a revised piece right now, and next year all of these Bills are going back up to the legislative during sessions. I need my family to push this shit for me and the prisoner population in Washington State:

#1) House Bill 1344 – Requires resentencing for people convicted as emerging adults (under 25 – that’s me)

#2) House Bill 1282 – Restoration of a universal 33% earned time accrual rate (this puts me out on my original case March 30th. 2022)

#3) House Bill1169 – 33% Earned time on enhancements and limiting stacking of enhancement (same as #2 for me)

#4) Senate Bill 5413 – Restrictions on use of Solitary Confinement

#5) House Bill 1413 – No use of juvenile points in adult sentencing (with other bills above puts me out NOW!)

#6) Senate Bill 5036 – Expansion of clemency and extraordinary medical placement

We got some love on education bills, graduated reentry, and voting rights, also the guys struck out on Robbery 2°, so we made some headway, but this coming year we need to push hard. Please vote, petition your legislature, and outside these courthouses and legislative buildings and DOC Headquarters to #FreeThemAll-WA, and join the Critical Resistance-Seattle, because the Resistance IS Critical my Family and Friends. Please get involved, and know that this Revolution to Dismantle, Change, and Rebuild this corrupt money pit called DOC is just getting started.

It’s time to Liberate our country from the 11th, and 13th Amendments.

Dismantle! Change!! Rebuild!!!

Critical Resistance-Seattle

#FreeThemAll-WA

C. Walter Weber

Tiller of the Earth

by Michael Henderson | Nov 19, 2021 | Daily Life in a Florida Prison, From the Inside

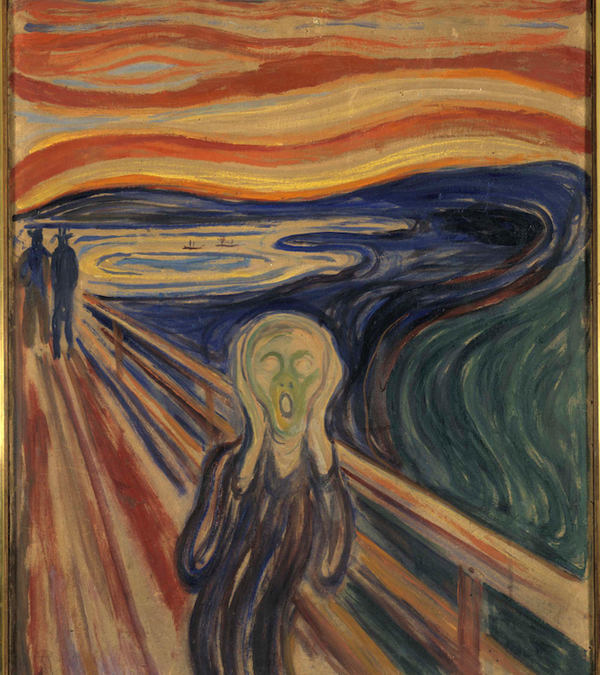

Edvard Munch’s iconic painting ‘The Scream’

Hello AI Family,

Have you ever been refused access to use the toilet? I mean without being held in a hostage situation like a bank robbery or a kidnapping. A very rare event. But even victims of those circumstances report receiving these basic humanitarian necessities. But not the victims of the white shirts of the Florida department of corrections.

These ”white shirts” as they are known, are any rank higher than a sergeant. Lieutenant, captain, major, colonel. Objectively, taking into account that there are people in the white shirts, and, at least ostensibly, they have reached a level of reasoning commensurate with the decisions they are required to make in order to maintain an already extremely stressed population of men, some of these folks still haven’t acquired the skill set to rationally make decisions to correct behaviors that are considered incorrect.

A description is needed here. In all prisons there are count times. Generally, the stock in these human warehouses are inventoried around five times during the waking hours of a day. The last waking count is known as a master roster count. We are allotted a ten or so minute regrouping period to retreat to our bunks for the count. This really seems like a never ending process some days. A couple of nights ago there was apparently a staff shortage and the white shirt on duty was in the dorm for count. I’m not sure that this particular night was one that required an extra minute to settle but all of a sudden the white shirt was screaming her lungs out, threatening to ”lock-up” not any offenders of her directives, but the neighbors of said offenders. Now remember that a lot of these men are here because they are unable to follow rules in the first place. So under a storm of vitriolic invectives these men are supposed to police each other. The end result could have very easily been a violent confrontation between any number of men — especially after the white shirt declared that we couldn’t use the toilets. Some tyrannical prison guards inflict this particular brand of power-wielding on their wards — either as in this case punishment for some perceived breach of their authority, or as a standard ‘I can do whatever the hell I want.’ At any rate, it can’t be healthy to keep someone from using the toilet. I would even suggest it falls under cruel and unusual punishment. But what I find even more striking is the perceived need to scream and yell threats of even harsher punishment for simple infractions at men who are already dealing with an almost impossible living condition.

According to the officer’s code of conduct, Fla. Administrative Code CH.33-208, this primitive coercive form of communication is strictly prohibited. As with primarily every other section of this code there is zero accountability. The ”professionals” are not held to their own standards of conduct, and yet, the wards are held to a heightened standard of not only their own conduct, but apparently the next man’s conduct as well.

The questions remain the same, ”Do you want your neighborhoods, your families and your loved ones to be safer? Do you want your incarcerated family and loved ones to reenter society better equipped to be a productive member of your community?” Our current modality of incarceration and non-accountability of the incarcerator will never achieve correction.

Much peace and love

Namaste’

by Rory Andes | Nov 14, 2021 | From the Inside

I recently read a book by Ryan Holiday titled The Obstacle is the Way, where he really digs into stoicism and how to bravely face adversity, a struggle, and use it to create something more. One chapter that struck me talked about “love everything.” I really had to sit on that. Love everything. Don’t bear with it, certainly don’t hide it or from it, just love it, whatever “it” is. How do I love the things chipping away at me currently? Of course I love the friends I have and the successes I find. I love my connections to the free world. I love that how I lead my personal life means so much more to me now than it probably has at any other point in my history. I work hard and I feel like I flourish in the hard work. I deeply love that. But prison? How do I love the obstacle of prison? Well, I can love knowing that, as pompous as it sounds and I don’t like that part of it, I’m not like the people who flourish in criminality (like, I get it… I’m IN a prison for reasons other than being saintly). But, I love the rebirth of my values, personal standards, and the emotional healing that emerged in prison. I love being able to foster extraordinary relationships with like minded people and I know I AM the company I keep, especially in a place like this. I can also love that I’m far closer to the end this sentence than the beginning. In the home stretch! I can love that! I love that someone gave me a voice to tell an audience these things from behind walls and I love the book-worthy situations I’ve found myself in, all while being sequestered from society. I love how I’ve grown and into whom here. And I love that throughout this prison time, I’m ok with being flawed, because it made me better. I’m human and I have setbacks from time to time, but it’s in those obstacles that I find things to love…

Of course, this is just one small aspect of this book. Leaning forward into the obstacles is the theme. Make them count. Make them memorable. Let them lead the way to success. From Thomas Edison, to Ulysses Grant, to Marcus Aurelius… all leaders of historical measure who knew how to use adversities as guideposts. But importantly, for me, the idea of love is what resonates the most. That’s something I can truly get behind…

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…

This review comes with a spoiler alert. If you chose to quit reading here any further, rest assured you will be pleased with the language, settings, and quality of character depicted on the pages of this book. Its style and prose is as quaint as an antique bookshop, complete with the commonality of typos. There is a remarkable amount of charisma to be found at 84, Charing Cross Road…