by Martin Lockett | Nov 22, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

It’s not too often that we take time in our day to reflect on the many good things we have: a job, healthy kids, a home in a safe neighborhood, food on the table, and the list could obviously go on for pages. After all, we are so preoccupied with the hustle and bustle of day-to-day affairs, doing everything we can to stay on top of our responsibilities; who has time to stop what they’re doing, ponder life’s blessings, and truly be grateful for them without thinking about what we need to get done the next day — or even an hour from now? But doing this is actually as critical as taking care of all the obligations we give so much of our attention to.

I have indeed found myself contemplating, more and more, the many blessings I have, even in my current circumstance which is inherently negative. But this is not entirely voluntary; allow me to explain.

I work for an addictions treatment program. Every day we start the group session with a daily reflection read from a book, and each person says why or how it resonates with him, followed by what is called a Daily Moral Inventory (DMI). When we check in for the DMI, each person says how the previous day went, what they’re grateful for, what they regret (if anything), etc. This expectation can at times seems repetitive, but I’ve learned that it’s a healthy practice to get into because if I were not “required” to do it, I likely wouldn’t “have time” to reflect on what I’m grateful for, in spite of my physical circumstance. Instead, I’d either keep my head down and stay focused on my job, my next goal, or find myself complaining about what is not going well in my life.

It’s entirely too easy to fall into a pattern of allowing good fortune in our lives to go unacknowledged as we focus our attention on the next goal or responsibility we want and/or need to carry out. This is a harmful practice, however, because it is essential to our psychological well-being that we take time to “pat ourselves on the back” for things we’ve accomplished, appreciate the things and people that make our lives more purposeful and fulfilling, and be grateful for opportunities that others have not had in life. Doing this has allowed me to refocus my efforts, while doing my part to “pay it forward.”

I intend to keep this practice of daily reflection and gratitude going even after I release from prison because it’s shown me how to ground myself on a daily basis. Life is entirely too short not to celebrate our good fortune and acknowledge how others have enriched our lives.

I take time to acknowledge and be appreciative that I can fulfill my dream of becoming a drug and alcohol counselor. I get to work for a successful treatment program in a prison setting, and teach groups and individuals about addiction and recovery, decreasing their likelihood to recidivate after they are released. I have had the rare opportunity to earn a Master’s degree in prison that, according to statistics, gives me a 0% chance to recidivate. Moreover, it enables me to go directly into my field with a level of credibility and respect that I never imagined coming into prison 14 years ago.

These are a few of the many things I take time to appreciate as often as I can. Life has enough struggles to complain about; therefore, I owe it to myself (as do you) to cast as much sunshine on my day as possible — by counting my blessings.

by Martin Lockett | Nov 8, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

We are no doubt in a time where evil has been on the rise, public discourse has turned hostile, demagoguery appears to be a winning recipe for political office, and the divides among demographics in our melting pot are as pronounced as I can remember in all of my thirty-nine years.

The recent tragic hate crimes and attacks on our nation’s politicians are, sadly, not new phenomena. What does feel different, however, is how accepted these acts are (often viewed as our “new norm”) by so many who have retreated to their tribal clans at the peril of our society at large. We have allowed our politics and innate compulsion to bind to our cultural groups, while excluding others, to cause our interpersonal/intercultural relations to either stagnate or regress. However, I’m reluctant to buy into the dismal notion that this is who we are, that perhaps we haven’t made as much progress as some of us thought.

We are a young relatively nation compared to many countries throughout the world. We have come from a period at the inception of this country that legalized slavery to now having had our first Black president. We have progressed from a nation that denied women the right to vote, to electing women to many of the highest offices in the land. We have grown from a country that denied Blacks and Hispanics adequate housing, employment, and educational opportunities to one in which young people of color graduate from prestigious colleges and go on to occupy high-level positions in distinguished companies. I could provide countless more examples to substantiate the progress we’ve made, but this is not necessary — the historical evidence speaks for itself.

The fact of the matter is that what we are currently seeing is a mere reflection of today’s political and social climate. Did you get that? Today. While it is unquestionably problematic, it is a snapshot in time — the peak of the current inflammatory political climate — and not reflective of how amazing, loving, compassionate, and truly genuine the majority of Americans are.

America’s true nature is especially on display when natural disasters strike and rip through our communities. What we inevitably see are Americans dropping everything to come to their neighbors’ aid. We see people rallying together, raising money, collecting clothing, and feeding those in need. This is who we are, and reflective of how far we’ve come. This is not to whitewash or downplay hate crimes that continue to pervade our communities, exacerbating already strained race relations. Having said that, it would be disingenuous not to acknowledge the steady stream of progress made over our country’s nearly 250 year history. We should not become prisoners of the moment by allowing what has happened in a matter of several months — or even several years — to represent what and who we are as a people, as a society. That is neither rational nor accurate. It would be no more accurate than to point to a temporary bad period in someone’s life (for whatever reason), as indicative of who they are. An objective judgement is based on how far someone has come in relation to where they started. Looking at America in this context, it is readily apparent how far we’ve come.

I sympathize with all those who are utterly disheartened by a rash of crimes committed in the name of hatred. I understand why many feel angry, depressed, and disgusted by a climate of tribalism. But we must remember that this is a moment in time in the grand scope of our societal evolution. Our focus ought to be on the overall progress made; and the historical evidence that shows we are better than this.

by Michael Henderson | Oct 31, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

Is Amerika preparing its children for a life in prison? According to the modality used by Sheriff Bob Gualtieri and his staff at the Pinellas County Jail to deal with violent inmates who prey on society, and then are housed with the general population inmates — the answer is absolutely, unequivocally, yes.

CNN reported today that a young girl who was being bullied by a group of troubled classmates was removed from her school’s roster and transferred to another school. As the parents filed suit, the school back-pedaled and said what amounted to – her punishment was for her benefit.

Here at the Pinellas constabulary, the method of dealing with violent, destructive bullies is to move them from housing unit to housing unit, maybe give them a time out, and then move them right back into general population to allow the cycle of violence to begin all over again.

There are a couple of disturbing factors that need to be examined in the penology mentality here and probably the most frightening is that if an inmate attempts to circumvent the cycle and protect himself with any kind of preemptive action — like getting staff involved to deter actual, physical harm by the violent predator — the inmate will likely be punished, as the story of the young girl reported by CNN.

This, like all my other accounts of life on the inside, is drawn from personal experience, and has happened to me recently. Equally frightening is the endemic culture of lies perpetrated by staff in order to cover what amounts to very personalized and branded justice. I have commented before on what could easily be construed as subjective reasoning for objective consequential happenings — but another issue that never gets talked about in Amerika’s dungeons is the brand of racism suffered by what arguably is the minority in prisons, the white or light-skinned prisoners. We hear all about the sufferings of black- and brown-skinned people, but here in the penal colonies the tables are often turned. That is precisely the case I have for your consideration.

An inmate who has been thrown out of every pod (housing unit) for aggressive, violent behavior, and threatening, abusive language was placed in our pod. I sought staff intervention for my own safety, as I’ve been the target of this young man before. The resulting action taken by Corporal Taylor was to tell me that it was my white ass that is the problem and I received a disciplinary report, was removed from my housing unit, and will be given time in confinement for supposed “manipulation of housing.”

This may not have been significant but for the fact that both Corporal Taylor and the violent inmate are black men. Why would a man with violent history not have had to be vetted before being placed with men he had been aggressive with in the past? The bigger question is why was the man who never had a violent incident in his life impugned and ultimately punished? The answer lies in the systemic divide and conquer mentality propagated by the staff at Pinellas County Florida’s jail and the statement made to me by Corporal Taylor.

There is no such thing as reverse racism. Racism is racism. Addressing these issues is never easy for either party when the very system that is supposed to be neutral and unbiased propagates for its own nefarious reasoning, the volatile environment that breeds hatred here in Pinellas Florida.

In closing, it should be noted that the inmate I was trying to stay safe from only lasted four days before having a violent, explosive outburst and was taken from the pod in handcuffs, while my pleas for justice are claimed to be lies from the top soldiers like Lieutenant O’Brien in Sheriff Gualtieri’s army.

Let’s open our eyes and watch this one!

by Eric Burnham | Oct 28, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

While certainly not as grossly unjust as it was prior to the 1980s, incarceration is still an incredibly dehumanizing experience, and given that people are incarcerated for years at a time, imprisonment in the United States often permanently scars a person to the point that many prisoners no longer feel like people at all.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m certainly not saying we are victims, and I’m not forming my conclusions based on the sense of entitlement that is so pervasive in American culture. It goes without saying that prison is punishment for criminal misconduct, and my actions warrant that punishment. I can accept that. I have developed into a man who can acknowledge the fact that my act of egregious violence not only cost another human being his life, but ultimately harmed everyone involved, including the victim’s family, my family, and the community at large. I am not denying that, nor am I blaming anyone else for my situation.

However, the commission of and consequences for a criminal act, especially an act of violence, doesn’t take place in a vacuum, right? I mean, in the same way that there are identifiable social and psychological ramifications for criminal activity, there are many social and psychological variables that influence and shape the reasons why a person commits a crime. Redemptive justice should look to identify and treat the highly individualized social and psychological deficits in those who engage in criminal activity in an effort to redeem the human beings behind the acts and prepare them for reintegration into society while simultaneously disciplining them with proportionate punitive measures. Unfortunately, prisons in the United States are neither redemptive nor restorative. They are overly punitive and dehumanize the already troubled human beings confined within them.

One example, a situation with which I am dealing currently is an increased emphasis on the enforcement of property rules on my unit, which is completely understandable because things have grown lax in recent years. I live on an incentive housing unit and we all had too much property stored in unauthorized places. However, the one in charge of communicating this elevated enforcement to those who run the units is less than approachable.

One day, he came to the unit after we were called to chow. We returned to chaos and intimidation — I entered my cell, and the folders I had on the table were thrown to the floor, my papers scattered, the blanket on the end of my bunk thrown to the middle, and as I surveyed the small room where I live, I could hear him threatening to move people off the unit when they simply tried to explain that this unit offers less storage space than other units. While this seems like a relatively innocuous incident, it is emblematic of a larger reality.

Another crucial aspect of being human is feeling warmth and love. The incarcerated are almost never shown warmth and love, and we rarely show it to each other. It is generally viewed as a weakness within prison culture, and the staff are trained to put on a persona that lacks any degree of warmth or compassion when dealing with us because it is believed that showing concern and warmth will reduce their authority, even though there is an argument that holds warmth would increase not only the authority and credibility of the staff, but also their safety. In an environment as cold and unfeeling as prison, it can become difficult to express warmth at all after a while. It just becomes so foreign, and if we are unaware of this dynamic, which most of us are, then it can become uncomfortable to receive it as well.

Every human being is unique and has a need to express his or her individuality, but in prison, our ability to experience and express our own individuality is limited. Communication is stifled. Staff rarely listen to or even allow us to explain our side of a given situation, believing we are trying to manipulate everything to our advantage. We are treated as if we are all the same, cattle to be exploited for profit by both the state and the private companies that do business within the prison system, rather than the unique human beings we are.

Meaning and purpose are also crucial aspects of being human. People need to feel like they matter; they need a reason to wake up, to put one foot in front of the other. The “Will to Meaning,” as Victor Frankl put it, provides the impetus for growth, the drive to become a better, more actualized person. While certainly not comparable to Frankl’s Nazi internment camp experiences, the dehumanization of contemporary incarceration still works against the will to meaning. The effects are simply more subtle and, therefore, more insidious. In fact, the prison system has no vehicle or mechanism either to express why meaning and purpose are so critical for rehabilitation or how to help the incarcerated find meaning and purpose in their lives. When humans are treated like their lives are meaningless, it becomes too easy to believe the lives of others are meaningless, too.

The punitive aspects of prison are out of balance with the stated mission of rehabilitation. Unfortunately, the current reality of the prison system is that it more often than not produces people who come out more broken than when they went in. They feel disrespected, frustrated, empty, alone, humiliated, and unloved. Academic and vocational training is limited in both scope and availability. Substance abuse or sex addiction treatment programs are literally non-existent, even though 75% of the incarcerated in Oregon are in for either a drug offense or sex crime. Although I’m not a sex offender, I was drunk when I committed an act of violence against another man, and I had a history of drug and alcohol abuse at the time.

Cognitive dissonance involves a psychological conflict resulting from incongruous beliefs and attitudes held simultaneously. The idea is that one cannot hold competing beliefs and attitudes for long — it is inevitable that a person will eventually take one position over the other. I feel like when this manager looks in the cells and sees pitchers full of ice water or colored sugary drinks, folders, books, and other evidence of human presence, it causes a psychological conflict for him because he does not view us as human. He wants no human possessions to be visible on the tables and walls — only steel and brick. He wants to see an animal in a cage, rather than a man in a room, so he reacts with venom, intimidation, and vitriolic rhetoric.

Problems of dehumanization are paradigmatic and systemic. Take for example the man in charge of pushing the elevated enforcement of property rules on my unit: It is not the enforcement of the rules that is dehumanizing. It is how he treats people as he enforces them. The lack of flexibility, nonverbal intimidation, and verbal threats reveal his cognitive dissonance regarding the incarcerated.

He is not the only one. Many administrative staff hold these views of the incarcerated, and because of the paradigm with which they do their jobs, subordinates adopt similar views, making it a systemic problem. I don’t blame them too much. I’m not sure they even understand the ripple effect they have on their world, but the consequences go far beyond themselves.

Constant dehumanization, experienced everyday in a thousand different ways over a period of years, amounts to socialization. The negative and abusive patterns of treatment during incarceration socially conditions the incarcerated to view themselves as less than human, unlovable, and undeserving of empathy, thereby reducing their capacity to empathize with those in society. In fact, gang members, sex offenders, and drug addicts who desperately want to change their lives find little in the way of guidance or counseling — when they are in that liminal space between their criminally-oriented past and whatever their future may hold, the only consistent message prison offers is that they are less than authentically human.

Sure, in this environment, we all have the choice to grow… or not, but the criminal justice system certainly does not highlight the better choices one could make. Nor does it show the incarcerated person how to purposely and positively alter his or her decision-making patterns in order to realize genuine change. This method of “rehabilitation” does not curtail criminal behavior or reduce the recidivism rate. Unfortunately, current models of incarceration and systemic dehumanization actually work to increase criminal thinking and antisocial behavior patterns. But…at least there is nothing on my table now.

by Eric Burnham | Oct 26, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

In the movie Shawshank Redemption, one of the incarcerated characters, Red they called him, went before the parole board. He had been in prison for over 30 years at that point, and one of the members of the parole board asked him, “Do you think you have been rehabilitated?”

Red responded. “I don’t know what that means…. I know what you think it means, but to me, it’s just a politician’s word, a made up word so people like you can have a job…” The setting of this scene is the United States in the mid-to-late 1960s. While it is undeniable that the criminal justice system has come a long way since the 1960s, I still relate to that scene.

I have been in prison since 2001, and I don’t blame anyone else for my incarceration. I am in prison as a direct result of my violence, my selfishness, and my irresponsibility. Yet, I have grown and matured in virtually every conceivable way, and I have made some observations about rehabilitation during my journey.

One of the stated missions of the criminal justice system is the rehabilitation of those convicted of criminal activity while holding them accountable for the harm they have caused. The concept of rehabilitation involves returning something back to good condition. Synonyms abound: overhaul, renovate, re-condition, restore, but it seems none of these truly capture what goes on in America’s prisons.

Without question, there are some programs that positively impact the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of those incarcerated, such as ABE/GED programs, a few basic cognitive-behavioral classes, and even some rudimentary mental health groups. However, none of them wield the depth or intensity to be considered authentically rehabilitative.

The greatest impediment to genuine rehabilitation taking root in the criminal justice system, in my opinion, is not only the ubiquitous tension between correctional staff and the incarcerated men and women whom they supervise, but also the fact that its magnitude is usually kept hidden — it isn’t ever talked about openly, making any solutions extremely enigmatic.

I certainly don’t hold it to be completely the fault of correctional staff. Without a doubt, they have a difficult, stressful, and often dangerous job, and they deal with some of the most unreasonable and violent personalities the country has to offer. The complexities and risks involved with being a correctional staff member do not escape me. I do question, however, whether the adversity and subjugation of the incarcerated escapes those who profit from them.

Genuine empathy and compassionate concern are transformative, not only for those to whom they ar given, but also for those who feel them when serving others. However, they cannot be applied legitimately to a correctional setting without an elevated degree of mercy from those who administer and enforce the rules, regulations, and orderly operations of a correctional facility. Unfortunately, mercy is often misunderstood, and within that misunderstanding lies the fundamental reason for the great gulf that exists between the incarcerated and those who staff correctional facilities.

Currently, much of the criminal justice system does little but warehouse and manage those convicted of crime, rather than treat the substance abuse and violence surrounding most criminal activity. This has created a growing underclass in the United States. During incarceration, “otherness,” “uncleanness,” and “inferiority” are internalized, and after release, pervasive disenfranchisement reinforces them. Mercy is too often perceived as letting someone off the hook or reducing consequences, to pull one’s punches, so to speak. Yet the true nature of mercy involves such a depth of compassion that one is moved to action on behalf of another. Holding those of us in prison accountable for our actions is both redemptive for us and demanded by the communities from which we come. Consequently, mercy requires justice — but the kind of justice prescribed by mercy is restorative, not corrosive.

Correctional staff are trained to put on a persona of authority and superiority when dealing with inmates and assert their authority at every opportunity. This maintains a social gap between themselves (essentially those who represent mainstream society) and the incarcerated, creating strawman stereotypes that make it incredibly easy to generalize the most negative notions of the worst incarcerated person to all incarcerated persons. “These guys are lazy, dirty, manipulative, untrustworthy, and dangerous.” These are statements made regularly about inmates by staff.

Instead of feeling empathy for the moral and social gulf that separates those who have lived a criminal lifestyle and those who have not, instead of learning more about the individual nuances that may provide insight into a given inmate’s behaviors, the situational assessments needed to do these things are too often abandoned in favor of what is easy: subjectively reconstructing the image of every inmate, replacing the diversity of motives and experiences with a singularity of favored presuppositions, a subtle form of rejection that affords correctional staff a feeling of superiority, which becomes intoxicating. This social distance facilitates thinking of the incarcerated in abstract, depersonalized terms.

Sure, we are not tortured — in fact, we are provided for quite well. But we are not treated with the dignity that might condition us to believe we could ever become contributing members of society. We often encounter an insensitive ear and a closed, even locked door when searching for redemption, intensifying the anguish, pervasive loneliness, and utter despondency of being separated from everything we know and love, and everything that knows and loves us.

However, the incarcerated are not blameless. Far too many incarcerated persons view their incarceration as an injustice, believing themselves to be victims, unfairly imprisoned. They operate with an obnoxious sense of entitlement, failing to acknowledge the wake of material and human carnage left as a result of their careless, selfish actions. They will spew anger and venom at correctional staff for the smallest, most inconsequential directive or request, however legitimate. Many inmates push the envelope, looking to manipulate every situation to their favor and even defraud their way into some sort of advantageous special treatment, and when their goals are thwarted, they will flip it, making the correctional staff into the bad guy. Some will even be violent, seeking to harm staff members in any way they can. Far too many incarcerated individuals are perpetually disrespectful, legitimately dangerous, and constitutionally unruly, shirking the authority of staff members at every opportunity.

This seems to be the result of the incarcerated doing the same thing the criminal justice system does to us: Inmates often dehumanize and objectify correctional staff, viewing them not as people with lives and families and a job to do, but as obstacles that keep us from doing what we want to do.

The bottom line is… no one is innocent in the creation of the tension between correctional staff and the incarcerated. These stereotypes are fundamentally inaccurate. All inmates are not irredeemable — some of us take responsibility for our hurtful behavior and are honestly interested in becoming people who do not hurt others in the pursuit of our goals. And neither are all correctional officers full of hatred for the incarcerated. Some are wonderful people genuinely interested in helping those inmates who are committed to becoming productive members of society.

The criminal justice system is broken, and the primary reason, aside from the obvious overcrowding as a result of draconian mandatory minimum sentencing laws and a failed war on drugs, is a vicious cycle of animosity between inmates and staff. And it makes it worse that we do not talk about it. Solutions to problems are not found in the dark. If we could all just give each other a break, accept each other as equals with regard to our humanity, and show compassion, things could really change for the better.

This past Friday, I was taking advantage of this amazing opportunity to take a CPR class. The lieutenant instructing the class actually spoke about this problem. He intimated that for many years he had seen only blue (the color of our uniforms) rather than our humanity. I was literally stunned! I was not offended; I was softened. We all know how we all feel, but when it’s brought into the open, it loses power. This staff member’s vulnerability earned my respect and afforded him a level of credibility that I have not often experienced in almost 20 years of incarceration — simply by acknowledging his struggle to see us as human beings.

I related to his words quite deeply because I deal with the same problem. For the past few years, I have felt my bitterness toward staff, this ball of galvanized disdain in my gut at which I have been chipping, trying slowly to process away my feelings by working to humanize the correctional staff. It has not been easy, but the admission by that lieutenant not only made it a little easier; it made my struggle feel normal as well, bringing me into the fold of society again, even if only just a little. I hope in the future we can do more to break down the barriers between us — after all, we are all human. Understanding that is what rehabilitation means… isn’t it?

by Melissa Bee | Oct 25, 2018 | From the Inside, News

We are beginning to hear from prisoners housed in Gulf Correctional Institution in the direct path of Hurricane Michael at the time it hit. They were not evacuated until days later. Below is a letter from one of them:

The hurricane was pretty crazy, at first I didn’t think it was going to be a big deal, but then I started seeing all kinds of debris flying around outside my window — metal roofs peeling back from buildings like sardine cans, and trees whipping around in the wind, so I changed my mind pretty quickly. When the eye passed over us, the officers evacuated all the guys from the open bay dorms (I was in a 2-man cell), and brought them to my dorm, so we had three people in each room for a day. The guy who moved in was telling me and my roommate how the roof caved in while he was on the phone with his mom, and the phone turned off on him. Once they decided to evacuate the whole prison, the officers forced everyone to leave all their personal property in the cells, so now that’s turning into a major ordeal. Everybody’s missing stuff, getting other people’s property, etc., It’s crazy.

My family (and others as well, I’m sure) is pretty upset that we didn’t evacuate before the storm, like we should have. What’s even more troubling is that for days following the storm, the media made it seem as if Gulf was OK. They showed pictures of a roof with some shingles missing, one partially twisted fence, etc. None of the buildings torn down to their frames or the trees snapped completely in half, the windows blown out of the dorms, or the flooded compound. I didn’t even recognize the place, it was so destroyed. The officers are telling us that Gulf is being patched up and we’ll all be going back in a couple weeks. I seriously doubt that place will be anywhere near habitable within months, let alone weeks.

by Melissa Bee | Oct 24, 2018 | book review, From the Inside

I read this book through two times. I enjoyed it so well that I developed an eight-week curriculum from this book, and as the Vice President of the NAACP here at Madison Correctional Institution, am in the process of preparing a proposal to purchase enough copies of the book to host the program.

The author writes about:

♦ Owning your choices – stop blaming others, and take ownership of your decisions.

♦ Sifting through brokenness – what has caused you pain throughout life?

♦ Forced change – we all endure change throughout life – how do you deal with it?

♦ Defining your life mission – who are you, and where are you going?

♦ Preparing for your “big move” – what changes are you going to make in life, and how will you ensure these changes lead where you are going?

♦ Organization – self explanatory, eliminate the clutter.

♦ Funds – are you setting money aside and planning financially for possible hardships in life?

♦ Investing in your life – are you paying what it takes to get where you want to go?

♦ “Pruning your life” – what people, places, and things do you need to cut loose?

♦ Networking – who can teach you what they did to get where you are trying to, by sharing their experience?

♦ Becoming an expert – learn all you can about where you want or what you plan to accomplish in life.

♦ Just a season – everything in this world is temporary.

♦ Quiet time – slow down and relax.

♦ Removing negativity – need I say more?

♦ Creating a winning mind – are your thoughts positive or negative?

♦ Volunteer for what you want – put yourself in position to gain experience and connections for whatever it is you want to do

Addional topics:

♦ Changing your pictures, finding a mentor, standing out, embracing failure, commit to consistency, changing the conversation, making a milestone out of your molehill, your personal standup comedy shows the beauty of the wait, your mirror moment, journaling your experience.

If you have faced any kind of hard times in the past, I recommend this book.

I am incarcerated at Madison Correctional Institution, in London Ohio. I am serving 26 to life while fighting to prove my innocence. I am ready to get out so that I can reestablish relationships with family, and become the father to my beautiful three year old daughter that I dream of being. I am devoted to family and my community in a positive manner. Society will see with their own eyes that these accusations are not the man I am. I admit that I was not a model citizen, and had some personal issues that I needed to deal with, but nothing I did warranted 26 to life. Please help me prove my innocence.

I am incarcerated at Madison Correctional Institution, in London Ohio. I am serving 26 to life while fighting to prove my innocence. I am ready to get out so that I can reestablish relationships with family, and become the father to my beautiful three year old daughter that I dream of being. I am devoted to family and my community in a positive manner. Society will see with their own eyes that these accusations are not the man I am. I admit that I was not a model citizen, and had some personal issues that I needed to deal with, but nothing I did warranted 26 to life. Please help me prove my innocence.

God Bless

Roger Black 729370

PO BOX 740

London, Ohio 43140

by Martin Lockett | Oct 22, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

Any woman in a relationship with a man in prison can attest to the fact that there will, unfortunately, be many in their families and inner-circle of friends who don’t approve of their relationships. Many who are critical of these relationships, however, are not coming from a place of experience or personal interaction with the incarcerated man, and therefore would give them a credible basis on which to judge him as a person — no. Rather, they operate from the standpoint of preconception, bias, and prejudice toward him — and anyone who is in his shoes — based solely on the fact that he is incarcerated. Simply put, they believe their friend or family member who is in this relationship can do much better, particularly with someone who is not locked up.

This is unfortunate because the fact of the matter is many good people reside behind bars — yes, I just said that. Most of us came to prison while in our addiction; this, however, is not nor was not reflective of who we are at our core. When forced to confront ourselves in a place of confinement such as prison, we tend to come to a place of honesty, growth, and for many of us maturity. We are in touch with ourselves and possess more qualities to offer in relationships than ever before; all we desire from those in society is a chance to be judged on who we are today. Unfortunately, many people disallow us this opportunity.

How sad it is that women who are in love with men in prison are denied the opportunity to talk to their girlfriends or family about their latest visit, phone conversation, or the amazing drawing, card or letter she recently received from her man. She knows any mention of him will be met with a scathing rebuke by some in her inner-circle. So, she is forced to keep it all to herself.

Why does she stay? they wonder. Why not leave him and find someone out here? they’ll ask. She tries to tell them she has met the man who understands her like no one else; that he is caring, sweet, and doesn’t judge her like many others do. She pleads with people she loves to just give him a chance to show he’s a good guy, but they’re not interested. Their minds are made up. As a result, she again shuts down and keeps them from her relationship lest they bring her down.

Here’s what I have learned: People with hardline positions who are not willing to have their positions challenged through experience are not going to budge one bit. They are intellectually lazy and emotionally stubborn. You can try to convince them to see something differently in the most direct or subtle ways, and they will refuse to be open-minded. So, for women in this type of relationship, when it comes to trying to get them to accept your man the way you see him — as a person deserving of a second chance — I would offer one rhetorical question: why even bother? You are wasting your time, energy and effort in trying to move an “immovable object.”

The best approach that will provide you with the most peace and serenity is to accept that they will be who they are; they will not give your man the benefit of the doubt. But, truthfully, that’s not what matters. What does matter is the fact you are happy and secure in your relationship. What should keep you going is the confirmation you get every time you talk to him, visit him, or receive a letter expressing exactly how he feels about you, how he tells you he can’t wait to spend every day outside of prison with you by his side. Let these sentiments carry you and comfort you in the midst of the unwarranted judgement and condemnation from those around you. Remember this: what others think about you is none of your business. What ultimately matters is what you think about yourself and your relationship. If both give you peace and happiness, then rest in that. Why bother trying to convince others they should feel the same way?

by Melissa Bee | Oct 21, 2018 | From the Staff, News

Boo

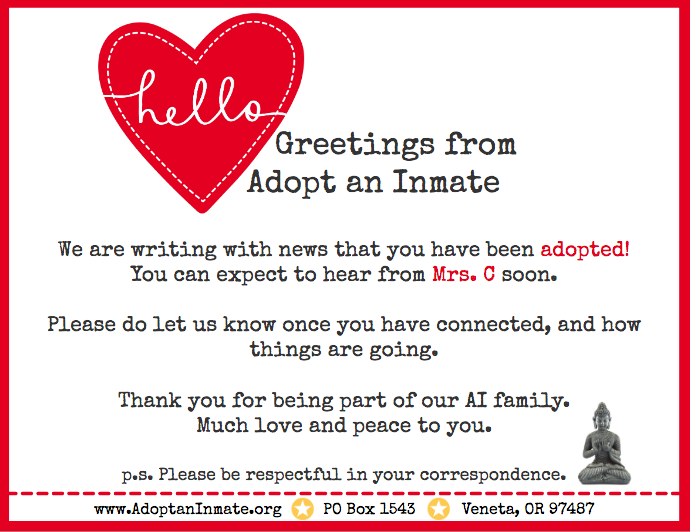

Greetings from AI!

If you’re like us, 2018 is speeding by – how is it already fourth quarter?

We haven’t checked in with you in some time, and wanted to send a quick update about what’s been going on behind the scenes, and what’s coming up.

News

♦ We recently surpassed our goal of 600 adopted inmates by the end of this year – at this rate we may hit 700 before 2019. Thank you from the bottom of our hearts to all the new adopters.

♦ For those who are still waiting, we appreciate your patience – you should be hearing more very soon. Feel free to check in by email to find out where you are on the list.

♦ Huge shout out to Amanda C, Cynthia H, and Tina L, for the countless hours you’ve put in helping clear out the new adopter requests. I wish I could pay you what you’re worth – you rock!

♦ The next issue of our quarterly-ish newsletter is in the works – watch your inbox!

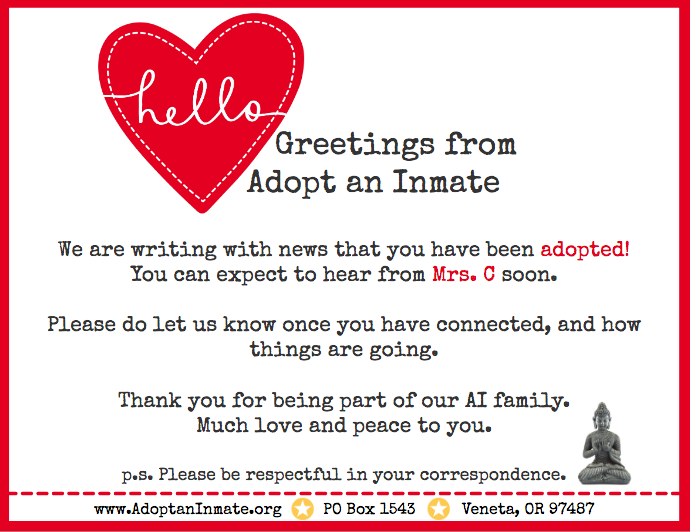

♦ We have some new contributors to our blog and lots of news to share in the coming weeks. Do subscribe so you don’t miss out on any new posts. Be sure to see today’s sweet letter from one of our adoptees, dedicated to his adopter, Mrs. C.

♦ Saving the best news for last – the founder of AI, my brother Rick, should be released early next year. He is the heart and soul of AI, and his constant support and guidance has been invaluable.

Thank you for being part of the AI family.

Melissa, Rick, Leah, Boo, and everyone at AI

by Boundless in the Midwest | Oct 21, 2018 | Inmate Contributors

“I is adopted!!!”

Not proper grammar, to be sure, but this was the response I sent Melissa when I got the news. The feeling I had was one of pure elation. It was as close to having a religious experience as I have had in a decade – so much so, that my total outlook since that day has only been positive. I have learned to feel joy again, to embrace hope.

In this current climate, it seems that good news, real good news, just doesn’t happen that often. I asked myself why, pondered the possible answers, and then asked myself why not? When I was a free man the only person who was truly responsible for my happiness was me. Oh sure other people could influence me and my moods but in the end it was my choice to be happy or not happy.

In prison I am told what to eat, when to eat, when to work, when to sleep and even when to use the restroom. Yes, even when to urinate. Every aspect of my life is controlled. Many of those over me feel they are not doing their job if they ever see me or another inmate smile. Yet I smile.

Do you wish to create some good news in the world? I know I do. Here is how you, just one person, can change the world. Adopt an inmate. It’s simple, pain-free and a great way to prove that one person can change the world.

Do you wish to create some good news in the world? I know I do. Here is how you, just one person, can change the world. Adopt an inmate. It’s simple, pain-free and a great way to prove that one person can change the world.

What adoption means is simply making a pledge, a commitment, to correspond with an inmate by snail mail or e-mail. You can give hope to someone who has lost faith in human compassion — to somebody who most likely has lost everyone they ever loved or cared about.

Everything about prison slowly strips your humanity away. Everything about prison teaches you not to trust anyone. It is a vicious cycle that turns men who made a mistake into career criminals and some men into worse. The average inmates I know developed an inferiority complex and began to resent society as a whole. We miss the real world so much that it turns into frustration and helplessness. All it takes to stop the trend is an angel with a few minutes to spare each month.

For many of us, it is as if time has stopped and we are trapped in a bubble. For me every day was February 12, 2012. I was broken until Mrs. C adopted me.

On April 7th, 2018, I received a polite, well-written e-mail from a complete stranger. It was short and to the point, but for me, a total stranger was treating me with respect. What? I had forgotten what it felt like to be treated like this. Mrs. C ended the e-mail with “All my best.” I was in shock. Later that day I received a second e-mail, and again Mrs. C was polite. She wrote me as if I were a long-lost friend who had merely lost contact with her, or so it felt. After I finally came out of shock, I was sure it was a mistake.

The following day I received an e-mail from Melissa from Adopt an Inmate, telling me I had been adopted by Mrs. C. It was after I reread that email for the fourth or fifth time that I realized the too-good-to-be-true woman who was treating me like a real person was true. GASP. It was not a mistake. I cried over the good news, then my clock started back up, it was no longer February 12, 2012.

I will forever be grateful to Mrs. C and dedicate this article to her. We e-mail back and forth a few times a week and I feel human again.

You want to change the world for someone? It can be done. It takes only a little effort. Mrs. C agreed to contact me once a month, but has gone beyond this. Thank you Mrs. C., for being a light in my darkness.

What adopting an inmate is not. It is not a dating service. It is not putting money on phone or commissary account or paying for a food box. You are not being asked to do anything more than treat a human humanely. You really can change the world by corresponding with one person.

You can talk about the weather, what famous movies were filmed near you, books, or trends. I suggest that politics and religion be avoided at all cost.

Inmates who get adopted should show respect for those who adopt them. Mrs. C is somebody I find witty and funny. I care not that she lives on the other side of the planet and I will never meet her.

A stranger has done for me what my family and friends would not.

I have once again realized that even in here, I am ultimately responsible for my own happiness. This is something my counselors have been saying for years. It took Mrs. C, her compassion, and her kindness for me to come to this conclusion on my own.

Thank you, Mrs. C., thank you, Melissa and everyone at Adopt an Inmate.

*Note: Boundless is correct, we ask for nothing beyond regular correspondence. We do have adopters who also choose to call and/or visit, put money on an inmate’s commissary account, send books or an occasional package. I have some adopters who send Christmas gifts to their adoptee’s children for Christmas or birthdays. All of these acts of kindness are appreciated, but not required.

We have a backlog right now, but with help from some dedicated volunteers we are working through the list, and continue to welcome all requests. If you’re one of the waiting adopters – expect to hear from us soon! Feel free to email us to see where you are on the list.

Do you wish to create some good news in the world? I know I do. Here is how you, just one person, can change the world.

Do you wish to create some good news in the world? I know I do. Here is how you, just one person, can change the world.